This is Gwen.

I’ve been working for a while now, in all my copious spare time, on organizing a fundraiser to help some dear friends. Given how closely to the bone my family lives from time to time, it may seem like an odd choice for me to use my time to make money for someone else, but my efforts aren’t about the money. The money’s just the most immediate way to begin righting a wrong.

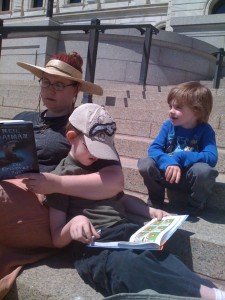

Elizabeth and Shreyas have two daughters. Nirali is two years old and completely adorable. And Gwen is eight, whip-smart with a smile as big as the world. Gwen is also autistic. Her family has had to pull her out of the public school where she’s been going since they moved to California because of its stubborn refusal to follow the Individualized Education Program (IEP) that outlines Gwen’s difficulties, goals, and the school’s obligations to help her function at her fullest capacity. IEPs are legal documents, and the school has broken the law time and time again by refusing to provide the support Gwen needs to learn and participate.

If her family just pulls Gwen from the school, with no follow-up, there will be no record of the egregious offenses the school district has committed. Another family with their own bright, high-functioning autistic child might run into the same obstinacy and intransigence, and never know that their experience is part of a pattern that goes back years.

The only way to change things in the future is to fight now. And fighting is expensive.

In return for donations to help Gwen’s family fund the legal fight and prove that a private school can do what the public school refuses, I’m putting together six months of new short fiction from a fantastic roster of writers. Every other Monday (with occasional “freebie” days at random), subscribers will get something new to read. Readers of fantasy, sci-fi, horror, and generally offbeat stories will recognize some of the authors who’ve already committed their talents: Matt Forbeck, Kenneth Hite, Josh Robern, David Niall Wilson, Cam Banks, Steven Savile, and more. Still more authors are still stepping forward; I’m thrilled and humbled by everyone’s generosity. You can subscribe right here.

But I’m not just doing this for Gwen and her family, much as I adore them. I’m not doing this just because it’s the right thing to do, though it obviously is. I’m doing this out of gratitude for the thousand little things my sons’ school does for them, above and beyond Connor’s IEP requirements.

I’ve written before about the misunderstanding, the ignorance, and the physically and psychologically scarring bullying Connor received from both administration and classmates at the school where he attended kindergarten. His Asperger’s Syndrome was so obvious to trained observers that, when we switched him to a different school for first grade, we were called in for a meeting about his diagnosis before the first month of school was over.

Over the years, we’ve had meetings upon meetings around that packet of papers labeled “IEP.” They’re full of jargon, full of measurable annual goals, services and modifications, assistive technology considerations, and other daunting phraseology. But that jargon translates into real help that makes a real difference. It gives him permission to walk out of any situation that’s overwhelming him to the point that he feels a meltdown coming on. It gives him access to tools like fidgets and weighted vests that allow him to focus longer and be more at ease in loud, crowded situations. It justifies the time spent in social skills group and occupational therapy, when other kids are drilling on academics that Connor mastered a grade or two ago.

All those therapies and tricks and tools are incredibly helpful. But the things for which I get down on my knees in thanks, and that I wish for Gwen and every other amazing kid trying to cope in this noisy, gaudy, overwhelming world with their quirky superhuman senses, are the things that aren’t ever written into an IEP. They’re the points of human contact, of compassion from professionals whose hands are more than full with the everyday concerns of all the other “perfectly normal” kids.

It’s the way that, when Connor had a meltdown at school after a week of substitute teachers and his mom in the hospital, the principal offered him a hug, and just held him as he sobbed under the weight of emotions too big and complex for him to sort out alone.

It’s the way that the school social worker offered to use “special funds” to buy a pack of undershirts so Connor didn’t have to wear the pressure vest that helps him stay calm on the outside of his clothes, where it might be noticed and commented upon by his classmates.

It’s the way that they recognized that his need for a break in the day could be fulfilled by an activity that would raise his self-esteem and make use of his extraordinary talents, and set up a schedule to act as a “reading buddy” to second-graders who could use a little extra attention.

And it’s the way that these amazing teachers and administrators are extending the same caring resourcefulness to Griffin, who doesn’t even have an IEP, but has needed help adjusting to kindergarten. They created a “job” for him, carrying a crate of books to the nurse’s office in the morning, and back to the classroom in the afternoon, to let him feel proud of helping as he gets some much needed movement breaks. It’s the special desk they made for him, with faux fur, sandpaper, and a bumpy silicone potholder glued to the underside for him to fidget with instead of constantly touching his classmates and their work.

A thousand little things that make our kids stronger, calmer, more confident, more self-aware, and better prepared for the thousand little things that none of us can foresee from day to day. Like those waterfalls of brightly colored ten thousand origami cranes, fashioned by hand from paper and love, a labor of such dedication that it’s believed to grant the recipient one wish. Except that the visible sign of the grace and compassion of these people isn’t as perishable and impermanent as paper.

It’s the fast, bright, smart, funny, kind, curious, and beautiful boys that their actions are helping to grow. Every parent and every child deserves an education that gives results like this.

That’s why I’m fighting for Gwen.

Domestic Engineering

Domestic Engineering  1 Comment

1 Comment

I saw my psychiatrist the other day for my regular check-in. As we went over the list of meds I’m taking, both those prescribed by him and those from other doctors, I said that the anti-depressant I’m on right now is working just fine, and that the only real change since I last saw him was that my pain management docs were having me transition from narcotic pain relievers for my fibromyalgia onto tramadol, a non-narcotic.

I saw my psychiatrist the other day for my regular check-in. As we went over the list of meds I’m taking, both those prescribed by him and those from other doctors, I said that the anti-depressant I’m on right now is working just fine, and that the only real change since I last saw him was that my pain management docs were having me transition from narcotic pain relievers for my fibromyalgia onto tramadol, a non-narcotic.