Game Theory, Psychology

Game Theory, Psychology  2 Comments

2 Comments Gamerography, Vol. 3: Wired to Play Differently

There’s finally a decent volume of literature out there about how women experience games–especially RPGs and video games–different than men. It helps all of us who’ve struggled to put words to the perspectives that we bring to the gaming table, many of which result in very different interactions with the rules, the stories, and the other gamers. And it provides writers and designers with insights that have changed the way games are written, so they allow more kinds of gamers to contribute to the collective interaction.

So I’d like to attempt to do something similar with another piece of myself that I bring to the gaming table. I have Asperger’s Syndrome, a difference in brain-wiring that places me on the autism spectrum. This part of myself is a relatively new discovery, but it’s undeniable and incredibly enlightening about things I could never otherwise explain. Many of these features affect how I experience creativity, social interaction, and collaborative work, three central pieces of the act of tabletop gaming.

The most important factor for me is my visual memory. I’ve written about my odd filing system before, but until the HBO movie about the life of Temple Grandin, I’d never seen my memory process outside my head. Because I have that visual catalog in my mind, I get incredibly vivid pictures from a multiplicity of contexts whenever someone invokes a place, a person, a costume, and a piece of equipment.

Practically speaking, this manifests for me in gaming in a number of ways. I have virtual battlemats in my head, and I can examine them from any vantage point, without needing minis or land/cityscapes (though I do enjoy the physical objects very much, too, for different reasons). I have pictures of characters and settings in my head that I literally inhabit. I know the size of my character’s bodies, how various features affect the way they move and sound. I assign them sensory features as well as hair and eye color, so I know how they smell and the close-up feel of their skin and clothing. They’re live, vivid people in real, textured places.

Another factor is my tendency to seek out patterns. It’s not compulsive, like someone with OCD might be; it is, though, automatic. For many autistic gamers, this allows them to understand RPG systems and make them do fantastic tricks, like a lion tamer making a beast jump through hoops. They see game systems as just another coding language that can be manipulated to perform the desired action.

Sadly, this is not me. I cannot grok systems unless the rules are so basically logical and self-evident, with a minimum of math, that they’re labeled “Ages 7 and up.” (No, I can’t explain this at all. I can at least read 10 different languages, so systems aren’t the problem, but math and I have a beef going back to 7th Grade.) As a consequence, character generation is agony unless it’s basically a single-step process, and I almost never play magic users. I vastly prefer cinematic, story-driven systems in which dice are only employed to give an edge of chance to the action I propose.

My pattern recognition talent gives me a different edge. First, I’m hell on carefully planned mysteries and adventures. One friend calls me the “storybreaker”–you can practically see the tire tracks where I went offroad, revealing options that never occurred to the author, in the ones that were eventually published. I don’t mean to circumvent plot devices; it’s a function of my autistic tendency to rapidly play through consequences to the Nth degree, thus eliminating options which I know will end in failure and generating other possibilities from that birds-eye view.

Second, I love pregens, even in systems that are entirely new to me. The words and numbers assemble themselves into 3D constructions in my mind. The closest I can come to a visual representation of this experience comes with the virtual reality models Tony Stark uses in the Iron Man movies to analyze maps, machinery plans, and crime scenes. (Here’s an example.) The alchemical process of “blowing up” a character sheet combines with my sensory memory to conceive a fully formed person almost instantaneously. I really wish you could see what this looks like–it’s pretty amazing from the inside.

The final factor I’ll mention in this post is my relationship with words. I’m hyperlexic (in short, far too many words for any and all things that pass through my head or mouth) and I’m a terrible show-off. Just as words form lifelike people and places in my mind, I love to craft my own contributions to the game with descriptions and dialogue, as vividly rendered as I can manage. Back in my days of MUSHing, the whole game was nothing but words on a screen, but I have scenes lodged in my memory that are so thoroughly illustrated and acted that I have difficulty remembering whether I saw them in a movie. And when I’m at the table, I can use the additional tools of vocal inflection, accents, gestures, and expressions, so my love of acting, connected to that vivid character in my head, can lead me to overplay my parts to a degree that might make other players uncomfortable. At least I don’t insist on staying in character while we take pizza breaks.

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con.

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con. The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.

The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.

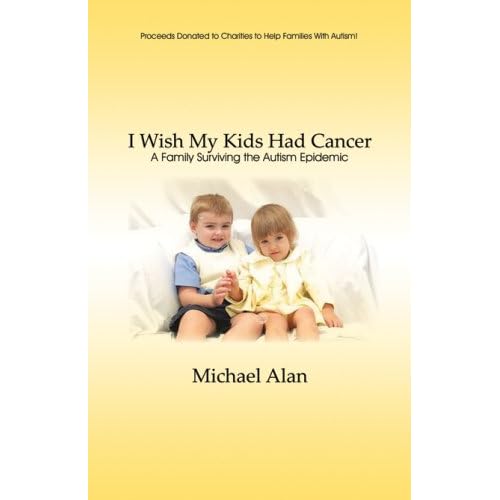

Friday is the Autistic Day of Mourning, a day to honor the autistic people who have lost their lives to the desperate or careless actions of parents and guardians, or to the crushing weight of the sensory world that seems inescapable by any other means but death.

Friday is the Autistic Day of Mourning, a day to honor the autistic people who have lost their lives to the desperate or careless actions of parents and guardians, or to the crushing weight of the sensory world that seems inescapable by any other means but death.

Or worse: you could end up like Mike Daisey. He’s a performer who got a lot of attention for a one-man show called

Or worse: you could end up like Mike Daisey. He’s a performer who got a lot of attention for a one-man show called

Almost every good and wonderful thing about the winter holidays is a sensory delight. The smells of cold snow and freshly cut pine and butter-rich cookies tingle in our noses. Pipe organs and French horns and jingly bells and heavenly choirs and crinkly paper delight our ears with musical sounds rarely used in the rest of the year. Velvety and satiny fabrics combine with delightfully scratchy sweaters and fuzzy hats in our special party clothes. We write ourselves dietary hall passes for the dozens of special, luscious holiday foods. And the lights…oh, the lights! Who doesn’t gasp and crane at the sight of an elaborately decorated building or brilliantly lit tree?

Almost every good and wonderful thing about the winter holidays is a sensory delight. The smells of cold snow and freshly cut pine and butter-rich cookies tingle in our noses. Pipe organs and French horns and jingly bells and heavenly choirs and crinkly paper delight our ears with musical sounds rarely used in the rest of the year. Velvety and satiny fabrics combine with delightfully scratchy sweaters and fuzzy hats in our special party clothes. We write ourselves dietary hall passes for the dozens of special, luscious holiday foods. And the lights…oh, the lights! Who doesn’t gasp and crane at the sight of an elaborately decorated building or brilliantly lit tree?