Foreign Language, New Zealand Studies

Foreign Language, New Zealand Studies  No Comments

No Comments Auck’ward: The Mother Tongue

This is my first attempt at writing about the multicultural society here, and it certainly won’t be the last. I’ll be learning the ways Maori and other Pacific cultures are embedded and interpreted in New Zealand for the rest of my life. I’m coming at this as someone who’s been a little more than casually interested for a long time, but who’s observing and experiencing the extent of indigenous culture on the broader New Zealand society for the first time.

New Zealand is a bilingual country, with all government publications and services bearing messages in both English and Maori languages. Kids learn Te Reo Maori (“the Maori language”) words, phrases, and songs from the day they enter school. Signs in libraries and community centers and public swimming pools are labeled in both languages. And many places retain their original Maori names.

The integration is more than official. Maori words crop up in Kiwi conversations all the time. Folks inquire about your family with “How’s the whanau?” Stores with calligraphied photo frames and plaques have “arohanui,” or “much love,” alongside the “love makes a family”-type stuff.

As someone who’s dedicated a lot of years to reading, writing, and speaking languages beyond English, I really love seeing Maori in print everywhere. I’m watching a bunch of shows on the Maori-language TV channels, and I’m working hard to get my pronunciation and vocabulary right. It’s the one part of indigenous culture where I have more clarity about what’s appropriative and what’s not.

Most importantly, though, is the fact that Maori’s omnipresence means that there’s no mistaking that indigenous people, their language, and their culture are alive and well, now and into the future. It’s a stark contrast with Native American people and cultures in America, where place names are obscured or unmoored from their origins, and Native people are rarely portrayed in the present day by mainstream media.

The differing paths of colonization have everything to do with this contrast. But New Zealand offers a vision for how language can be used to stitch together the past and present and offer a way forward as a bilingual and bicultural society.

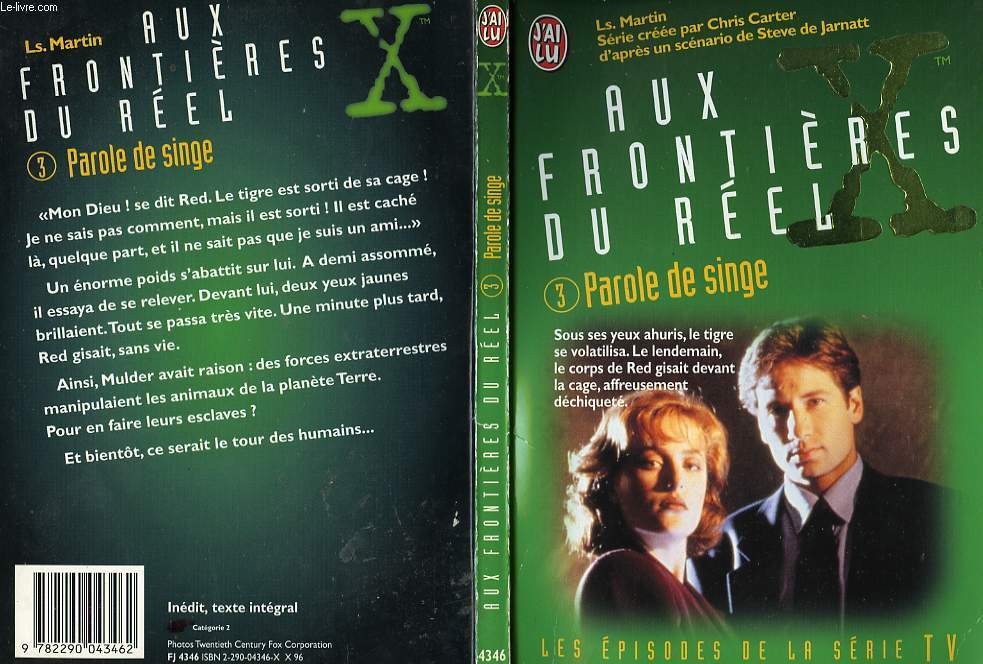

But she was right. Nicolas was a real live French gamer guy. I thrilled him in our first meeting by having Secret Knowledge. We were talking about TV shows, movies and books we liked, and he asked if I watched “Aux Frontières du Réel,” or “On the Frontiers of Reality.” I said I didn’t know it, was it French? “Non, non,” he insisted, and reached for a book. The cover explained it all—behind the French title was a distressed, typewriter-style X. “Oh,” I explained in French, “In America it’s called ‘The X-Files.’” “That explains everything!” he exclaimed. “I always wondered why that X was there!”

But she was right. Nicolas was a real live French gamer guy. I thrilled him in our first meeting by having Secret Knowledge. We were talking about TV shows, movies and books we liked, and he asked if I watched “Aux Frontières du Réel,” or “On the Frontiers of Reality.” I said I didn’t know it, was it French? “Non, non,” he insisted, and reached for a book. The cover explained it all—behind the French title was a distressed, typewriter-style X. “Oh,” I explained in French, “In America it’s called ‘The X-Files.’” “That explains everything!” he exclaimed. “I always wondered why that X was there!” I’d only seen Doctor Who played by Tom Baker on PBS, when I was about five years old. What I’d seen, I didn’t really remember, except, of course, the scarf, and several aliens that looked like upended rubbish bins on wheels. I’ve become a rabid fan since the 2005 reboot, and there’s no doubt I would’ve enjoyed the game more, knowing what I know now.

I’d only seen Doctor Who played by Tom Baker on PBS, when I was about five years old. What I’d seen, I didn’t really remember, except, of course, the scarf, and several aliens that looked like upended rubbish bins on wheels. I’ve become a rabid fan since the 2005 reboot, and there’s no doubt I would’ve enjoyed the game more, knowing what I know now.