I’ve been working on the campaign for marriage equality here in Minnesota since March, and as I’ve written before, it’s the most fulfilling political, social, and activist project I’ve ever worked on. I’m a total addict to the amazing people and experiences I encounter every single time I put in some time, and I’m going to crash hard on November 7, even if we manage to win. I’m already getting the shakes. Last night, I asked my friend and co-trainer Scott, who works in politics for his day job, for a new campaign–I’m lining up a new dealer once Minnesotans United for All Families skips town.

I’ve been working on the campaign for marriage equality here in Minnesota since March, and as I’ve written before, it’s the most fulfilling political, social, and activist project I’ve ever worked on. I’m a total addict to the amazing people and experiences I encounter every single time I put in some time, and I’m going to crash hard on November 7, even if we manage to win. I’m already getting the shakes. Last night, I asked my friend and co-trainer Scott, who works in politics for his day job, for a new campaign–I’m lining up a new dealer once Minnesotans United for All Families skips town.

MN United has built a campaign unlike any other, rejecting the messages and tactics that have failed in 30 states where anti-marriage amendments have gone up for a popular vote. While talk about the rights and benefits that attach to marriage, and how the denial of those rights amounts to separate-but-equal discrimination on par with civil rights fights of the past, are important to many supporters of marriage equality, they aren’t generally persuasive for people who are on the fence about gay marriage. So we’re having personal conversations with voters, using our own life stories, to make it clear that marriage is about love and commitment, no matter the gender of the partners. These stories are powerful, and they change hearts and minds and votes.

Only four days remain until the election, so I’m going to share the core of the conversations I’ve been having with you today. If you’re in one of the four states voting on marriage equality, I hope that this strengthens your resolve if you’re a supporter, and opens your heart to the conversation if you’re still undecided.

Our first walk as Mr. and Mrs. Banks, 5 October 1996

I find this amendment personally hurtful on so many levels. I have the great good fortune to be married to the love of my life, despite the astronomical odds that we would ever find one another on opposite sides of the world. And for the last sixteen years, we’ve had each other in good times and bad. I’ve rejoiced in the affection and the support and the million inside jokes and shorthand references that weave us closer, and I’ve buckled with relief into that tightly knit fabric of partnership in the times of crisis and grief. I think marriage is the best game in town, and I devoutly wish the same celebration and endorsement for every loving, committed couple who lean into the unknown future together.

All of this hinges, though, on one critical fact: my beloved was the opposite gender. When we fell madly in love, we had many obstacles to overcome so we could be together, but the legal right for me to marry him and secure his immigration status so we could start our new life together was not one of them. We obtained a K-1 “fiance” visa that allowed him to enter the country and get on the fast track for a green card by submitting evidence of our marriage. We went through the separate interviews to assure our marriage wasn’t a scam.

But I’m bisexual. There was no guarantee that my soulmate would be a man. And if he weren’t, the last sixteen years–all the love, all the progress, all the family we’ve built–disappear. That one thought blows through my gut like an icy wind and fills me with unbearable sorrow. I cannot imagine the pain and devastation of being told I couldn’t marry and be with my beloved.

And I look at my amazing, difficult, brilliant, gorgeous, perfect sons, and I marvel even more. We didn’t have to submit any applications or pass any interviews before we decided to conceive them, and not once have we ever had to fear that they would be taken away from us. We’re far from perfect parents, but no one has ever questioned whether we’re the best people to raise them. It’s assumed that they’re safe and happy and healthy and loved, and there’s no awkwardness when I introduce their other parent at school events or church functions.

Believe me, all this “traditional”-ness is positively mortifying to a weird, eclectic nonconformist like me. Frankly, it’s embarrassing. We didn’t set out to create a “traditional” family, and we’ve done everything in our power to the least traditional traditional family around. But we are very aware of our privilege, and there’s no reason in the world it should be reserved to our narrow demographic.

Believe me, all this “traditional”-ness is positively mortifying to a weird, eclectic nonconformist like me. Frankly, it’s embarrassing. We didn’t set out to create a “traditional” family, and we’ve done everything in our power to the least traditional traditional family around. But we are very aware of our privilege, and there’s no reason in the world it should be reserved to our narrow demographic.

Marriage is an important but limited part of how I envision family. I’m a child of divorce, and even as an eight-year-old, I knew that my mother and father weren’t working out. I knew that marriage stood in the way of being our best selves, and I told my mom often as a kid, then a teenager, then an adult, that she made the right call. That divorce didn’t dissolve the ties of family, though–I’m still close with my father’s family, and I kept my birth last name as a second middle name when my stepdad adopted us years later. But I also watched my grandparents’ marriage, which started with my grandma saying, “I’ll marry you so I can get out of the house before I kill my sister. But if it doesn’t work out, you go your way, I’ll go mine, and no hard feelings.” It lasted 62 years.

We teach our sons that families come in all shapes and sizes. Of course, we didn’t have to work too hard to teach them this: they already knew it. They have friends who have a mom and a dad like they do, and friends who only live with their mom or their dad, or travel between their parents’ houses. They know friends who live with extended family, or foster parents, or adoptive families. And they know friends with two dads or two moms. All they care about is that their friends are as loved and secure as they are.

So I’m voting no.

I’m voting no because I treasure my marriage. No other word in our language and society so completely sums up the lifelong commitment and enduring love that I share with my partner, and it hurts to imagine being told that we didn’t qualify for that word by something we couldn’t change or improve. My marriage is strong, and no married gay couple down the street, arguing about bills and chores like we do, makes that less secure.

I’m voting no because I hold my sons in hope and love. I feel that they’re better people because we’ve taught them that every person is worthy of the same dignity, no exceptions. My dream for my boys is to dance at their weddings, and the only thing I care about is that the person they marry loves them as much as I love their father. I’m going to dance, it’s going to be Bad Mom Dancing, and it’s going to live on in infamy on YouTube, to forever embarrass them, like every good mom should.

I’m voting no because my understanding of the world’s faiths teaches me that the most universal truth among humans is to treat one another the way we would want to be treated. Whether it’s the Judeo-Christian Golden Rule, or the Confucian Silver Rule, this is held as a central tenet. We rarely follow the ancient scriptures that prohibit same-sex partners on other subjects; we acknowledge that they’re historical documents, and that society’s values have evolved since they were written. I want my church to have the religious freedom to marry gay and lesbian couples as our faith embraces as equally entitled.

I’m voting no because I’m a historian. I can see that the institution of marriage predates the Bible and that it began as an economic transaction to link families and secure heredity. It was not always a sacrament, and it was not always available to every heterosexual couple. It hasn’t “always been” any particular way. Marriage for love is a damned newfangled idea, relatively speaking. If you married someone not from your hometown, you’re already breaking “traditional” convention, let alone someone of a different church, faith, ethnic group, or race.

I’m voting no because I’m a teacher and a parent, and the health, safety, and wellbeing of every child matters to me. I can’t imagine the horror of waiting to know how the state where they were born is going to vote on whether they and their families are welcome. LGBT youth are so fragile already, under siege in schools and churches and media, and it’s a sacred trust we are given to show them that they can aspire to fully participate in society and experience the range of human love. I have great confidence that other teachers will continue to teach age-appropriate lessons, and that as parents we still have the greatest power to teach our children about morality.

I’m voting no because I’m a patriot. I believe in the founding principles of our country, especially the purpose of our constitution as a document that secures personal freedoms and limits government intrusions. The constitution should never be used to carve out a segment of the population and deprive them of the same liberties as others enjoy. And we certainly shouldn’t be putting rights up for a popular vote. Ideological conservatives have made some of the most persuasive arguments along these lines.

I’m voting no because I’m an optimist, and I believe our society is moving toward a broader, more inclusive understanding of one another. The less we allow race, gender, faith, class, and sexual orientation to cloud our vision of a common humanity, the more we will recognize that we all want the same thing. We’ve got a long way to go on all of those issues, but we can (and should!) work on them simultaneously. I reject the arguments of fear, division, and misunderstanding, and I put my hope in the journey we’re on toward life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Uncategorized, World Religions

Uncategorized, World Religions  No Comments

No Comments

Religion is a tricky thing. I should know–on a variety of levels, I’ve been studying the features and interactions of religion since I was a little girl. In fact, I made a profession of it, quite by accident, as

Religion is a tricky thing. I should know–on a variety of levels, I’ve been studying the features and interactions of religion since I was a little girl. In fact, I made a profession of it, quite by accident, as  But, as

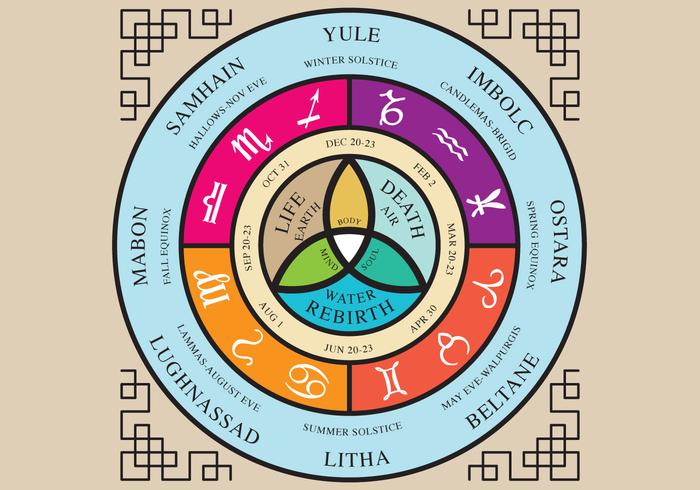

But, as  The facts of my faith, on the other hand, are these: I feel a deep, ineffable connection to ancient generations through the rituals and beliefs I hold dear. I am part of an endless continuum of women and men who have marveled at the beauty of the waxing moon, or tasted the similarity between sea water and tears, or celebrated the first point at which the days become perceptibly longer. Nature is my religion, the forests my cathedrals, the fields and shores my pilgrim paths. That biology and astronomy and physics and geology all mingle to create the singular experience of life on this planet is all the mystery and wonder my soul needs.

The facts of my faith, on the other hand, are these: I feel a deep, ineffable connection to ancient generations through the rituals and beliefs I hold dear. I am part of an endless continuum of women and men who have marveled at the beauty of the waxing moon, or tasted the similarity between sea water and tears, or celebrated the first point at which the days become perceptibly longer. Nature is my religion, the forests my cathedrals, the fields and shores my pilgrim paths. That biology and astronomy and physics and geology all mingle to create the singular experience of life on this planet is all the mystery and wonder my soul needs.

When I was in college, I had the great good fortune to see Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. speak on campus. He was as hilarious, irreverent, and insightful as his books. I wish I remember more of what he discussed, but just one thing has survived the years and leaks of memory.

When I was in college, I had the great good fortune to see Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. speak on campus. He was as hilarious, irreverent, and insightful as his books. I wish I remember more of what he discussed, but just one thing has survived the years and leaks of memory.

The time for ritual is at hand. I stand in the place of my power, tools of the magic I will work laid out before me– silver, wood, and steel. Fire and water are at my command, earth and air held back by my will. In this time, I will draw on the forces of creation, shaping elements. Here, I am an alchemist, a hand of the goddess herself.

The time for ritual is at hand. I stand in the place of my power, tools of the magic I will work laid out before me– silver, wood, and steel. Fire and water are at my command, earth and air held back by my will. In this time, I will draw on the forces of creation, shaping elements. Here, I am an alchemist, a hand of the goddess herself. While I am not so bold as to commit to such a statement myself, the power of the kitchen, and what it summons and creates, is not to be denied. Though I began down the path of Wicca in solitude, I learned the magic of cooking as all good magics are best learned : at the elbow of a wise and laughing grandmother. The rules were simple. Wash your hands. Clean as you go. Read the whole recipe before you start. Measure with care. And, most importantly, share the joy as often as possible–that’s why there are always enough beaters and spatulas and bowls for everyone. If you abide by that last rule, no spills or scorches can spell failure. Just vacuum up the oatmeal, wash the egg out of your hair, and laugh about the fun you had.

While I am not so bold as to commit to such a statement myself, the power of the kitchen, and what it summons and creates, is not to be denied. Though I began down the path of Wicca in solitude, I learned the magic of cooking as all good magics are best learned : at the elbow of a wise and laughing grandmother. The rules were simple. Wash your hands. Clean as you go. Read the whole recipe before you start. Measure with care. And, most importantly, share the joy as often as possible–that’s why there are always enough beaters and spatulas and bowls for everyone. If you abide by that last rule, no spills or scorches can spell failure. Just vacuum up the oatmeal, wash the egg out of your hair, and laugh about the fun you had. But I have to be honest about something, and it’ll probably blow the lid right off any sort of “kitchen witch mystique” I may have managed to build. I am no gourmet. I’ve never taken a cooking class. Those brownies which my friends and co-workers steadfastly maintain are the best they’ve ever tasted? Betty Crocker, Fudge Supreme, $2.49 with coupon. That chili whose aroma wafts out like tickling fingers when I open the door on a cold winter night, drawing my husband in all the quicker? Packet of spices, canned beans and tomatoes. Simmer on low for 20 minutes. That’s it. And I’ve never made a secret of it.

But I have to be honest about something, and it’ll probably blow the lid right off any sort of “kitchen witch mystique” I may have managed to build. I am no gourmet. I’ve never taken a cooking class. Those brownies which my friends and co-workers steadfastly maintain are the best they’ve ever tasted? Betty Crocker, Fudge Supreme, $2.49 with coupon. That chili whose aroma wafts out like tickling fingers when I open the door on a cold winter night, drawing my husband in all the quicker? Packet of spices, canned beans and tomatoes. Simmer on low for 20 minutes. That’s it. And I’ve never made a secret of it. So I may not always remember all the poetic invocations when I call the Watchtowers in a Circle, but I remember the favourite food for every loved one in my life, and most of the recipes. And so I might be dreadful at keeping a proper herbal grimoire stocked–my spice racks are the envy of all who survey. I consider myself well on the road to the Lord and Lady’s wisdom, because I know the seat and value of a generous, abundant power within myself, one of the greatest signposts on everyone’s spiritual journey. And when I get there, I’ll be sure to have a dish to pass.

So I may not always remember all the poetic invocations when I call the Watchtowers in a Circle, but I remember the favourite food for every loved one in my life, and most of the recipes. And so I might be dreadful at keeping a proper herbal grimoire stocked–my spice racks are the envy of all who survey. I consider myself well on the road to the Lord and Lady’s wisdom, because I know the seat and value of a generous, abundant power within myself, one of the greatest signposts on everyone’s spiritual journey. And when I get there, I’ll be sure to have a dish to pass. I’ve been working on the campaign for marriage equality here in Minnesota since March, and

I’ve been working on the campaign for marriage equality here in Minnesota since March, and