I’ve been trying to string these observations together for three days now, and failing utterly to find a single narrative thread. But I really feel the need to get these ideas out there. So, instead of a coherent blog post, you get a bunch of random thoughts about the complexities of race relations. My apologies.

******

Rev. Mark Morrison-Reed and me, May 2012

I’m thinking a lot about race these days. Part of that is deliberate. I took part in a study group about the racial history of my religion, Unitarian Universalism, at church, in anticipation of a weekend visit by the foremost historian of the African American UU experience, Mark Morrison-Reed. We read his book, Darkening the Doorways, and discussed everything from white privilege, to assumptions about what black visitors to our church would find welcoming, to outreach efforts to walk the talk on multicultural engagement.

The accompanying workshop, and the extended conversation for the group of us, was difficult and painful, but soul work really should be. The first principle of our faith is that we honor the inherent worth and dignity of every person, but we’ve been unsuccessful more often than successful at truly embracing real diversity in our church homes. We’re so much more comfortable going into communities of color for a day of service–us doing things for them, not with them–then returning to our monochromatic congregations on Sunday with the glow of righteousness.

The main conclusion we came to that day, with Mark’s help, is that communities of color are used to people coming and going. What they’re not used to is people staying. Volunteers paint buildings and plant gardens. They don’t come back to touch-up or weed. It’s the same with political work. Don’t just show up for the march–come back for coffee, stay for dinner. Don’t just make speeches–ask what they want, and listen as long as they want to talk.

******

I’m not colorblind. My stepdad says he is, with ridiculous statements like, “I don’t see race” and “There’s no such thing as black and white–we’re all cocoa, vanilla, cream tea, cinnamon.” It sounds delicious, but it’s hard for me to reconcile this kind of obliviousness with his history as a young white man who stood up for civil rights in the ’60s. He even attended Dr. King’s “I Have A Dream” speech. To me, this is blindness, not color blindness, and it diminishes the real struggle people of color have had and continue to have in America. Is this a relic of that generation of liberal speech on race? Did it sound as insensitive in the past as it does now?

******

I see race because I see patterns. As a kid, I was curious about things like melanin, epicanthic folds, and naso-labial shapes. But I was far more fascinated by the differences than worried about them. I noticed that people of different ethnicities smelled differently, and I wanted to taste the food I scented on their clothing and in their hair. I collected dolls dressed in the native costumes of different nations. I spent hours in a Chicago-area children’s museum, acting out family life from Fiddler on the Roof in the kid-sized Jewish home, and making tortillas and touching all the weavings in the Mexican home. And my mom tells me that, around the age of 2 and 3, I would babble incessantly in some weird language, then sigh in exasperation when she told me to stop talking nonsense. “*Mo-om*, it’s not nonsense,” she says I said, “I’m speaking French.” To this day, she wishes she’d known someone who spoke French, to find out if I actually was.

******

I worked in a record store at the last year of my undergrad work, in Lawrence, Kansas. I loved my job, but I’d watch the kids who browsed a little too long in the Rap/R&B section. The white boys were so stupidly obvious, all I had to do was walk up to them and ask them how I could help to get them to mumble nervously and quickly leave the store, their shoplifting plans foiled. When it was young men of color, I’d watch them, then deliberately turn away, telling myself it wasn’t fair to profile them thus. After they left, I’d do a quick check of the section, and when I found neatly razorbladed magnetic tags or plastic wrappers stuffed into the corners of the racks, I was furious and hurt. I hated that they reinforced the negative stereotypes, justified my profiling, and made me feel racist and ashamed.

******

I just read a book by John L. Jackson, Jr. called Racial Paranoia: The Unintended Consequences of Political Correctness, in which he makes a compelling case that, in the wake of the advances at exterminating de jure (in the law) and de facto (in reality) racism, all the remaining ambivalence gets internalized into what he calls de cardio (in the heart) racism, which isn’t even always conscious, and will be much harder to stamp out. Jackson posits that, if people on both sides of the color line can’t trust people to speak the truth about race, they come to mistrust everything they say about race, leading to deep racial paranoia.

Mind=blown.

The book taught me about the propensity to believe in vast conspiracies, based on this fundamental mistrust, and the books and music who advance these theories in the black community. I felt about a dozen questions and observations snap into place, finally in context, with each chapter. And his theory confirms my suspicions about the direction public attitudes about LGBT folks are headed, as it becomes increasingly less acceptable to openly discriminate. In this way, among so many others, we have to acknowledge that civil rights are civil rights are civil rights.

******

Few things make me as frustrated or embarrassed as seeing white people co-opting pieces of other cultures as their own. Purely Euro-American people drumming in sweat lodge retreats at expensive resorts. Suburban soccer moms who say they understand Latinos because they’re sending their kids to a Spanish-immersion private school. Kids putting on the swagger and language of inner city culture, without having to suffer any of the doubt and fear that comes with walking through gated communities while black.

A few years ago, I heard someone ask, “Why is cocaine so addictive and damaging, when South Americans chew coca leaves for years and never suffer ill health?” The answer is simple. Because when you take something out of context–extract, distill, purify–you may amplify the parts you want, but you lose hundreds of organic compounds that balance and mitigate the downsides in ways we don’t even fully understand.

Culture works the same way. When you sample ideas and practices out of context, you may feel enlightened and energized by your new, hip, exclusive experience, but you’re missing the point, and denigrating a culture that’s richer than you even know. Admire Native American spirituality? Learn about rez life. Like to sing African American spirituals? Learn about the black experience of Christianity and liberation theology. Do the work, and learn the context.

******

I’m not trying to “put on” blackness, with all these inquiries into race lately. I want to understand a culture that is, in so many ways, hidden in plain sight. I want to understand how people of color experience the same things I experience, each of us through our different lenses. Those lenses are ground by things like dinner table conversations, schoolyard lessons, the looks you get (or feel) walking down the street, and how it feels to stand on thresholds real and metaphoric.

I’ve experienced the world through the lens of white privilege; I know that deep in my bones. I don’t feel guilt, but I do feel regret. I’ve also experienced the world through the lenses of being female, being autistic, being liberal, being curious. I want to hear the voices, and I have a deep desire to reach across that divide, as much as I would be welcomed, to speak to and embrace the common humanity of us all. I’m not satisfied with the boundaries others tell me are “safe.”

******

I am happiest when my world is diverse. And I want my boys to grow up thinking that friends come in every shape, gender, color, physical ability, and personality. When they were younger, I took them to the parks where the immigrant families came for day trips, up from Chicago. A lot of the locals in our lily-white resort town told us to avoid them on weekends, but I wanted my sons to smell different cooking, hear different languages, and play with every kind of kid. So many families welcomed my wild, gregarious sons, and seemed delighted with the mingled laughter and fun of their children and mine.

When they ran over to ask if they could play with a new friend, I asked them to point out at least one of the kids’ parents. They would point vaguely, eager to return to the game, and say, “His dad is the one in the green shirt” or “His mom has long hair.” I would follow their little pointing finger, and as often than not, the man in the green shirt was also black, or the woman with long hair was dressed in a sari. But those things didn’t register as different enough to remark upon, and skin color was irrelevant, next to the possibility of a new playmate.

Am I wrong to be proud of that? I don’t want to seem self-congratulatory. But teaching values to kids is such a fraught proposition, and the way they treat others–especially perfect strangers–is one of the real litmus tests for whether your lessons are sinking in. They’re a big part of why I want to expand my circle of friends and contacts to include more people of color. The indifference to difference doesn’t last forever. It’s time for me to put my body and heart where my values are, for them to see.

Social Studies

Social Studies  1 Comment

1 Comment

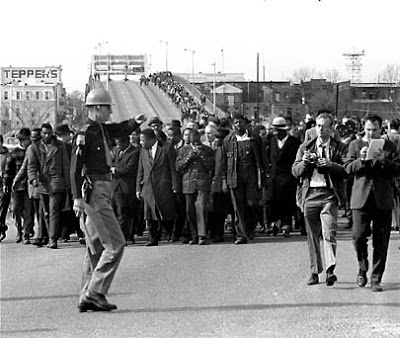

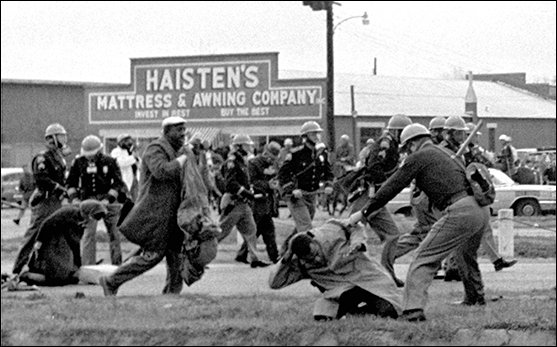

35 years later, I’m not sure I understand any better. I still fail to understand why white people treated them with disdain and cruelty and brutal indifference. I fail to understand why white people still treat black people that way.

35 years later, I’m not sure I understand any better. I still fail to understand why white people treated them with disdain and cruelty and brutal indifference. I fail to understand why white people still treat black people that way.

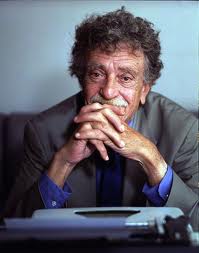

When I was in college, I had the great good fortune to see Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. speak on campus. He was as hilarious, irreverent, and insightful as his books. I wish I remember more of what he discussed, but just one thing has survived the years and leaks of memory.

When I was in college, I had the great good fortune to see Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. speak on campus. He was as hilarious, irreverent, and insightful as his books. I wish I remember more of what he discussed, but just one thing has survived the years and leaks of memory.