Physical Ed

Physical Ed  5 Comments

5 Comments This Belly

This belly is fat, and it’s mine. I own it. I earned it.

And I hate it.

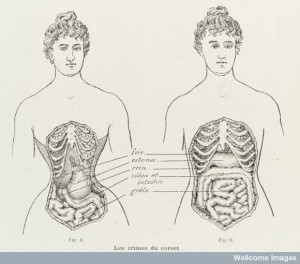

I feel it around me like sandbags as I walk and sit and lie down. It oozes over my waistband. It forms doughy rolls inside my shirt. It pushes clumps of flesh into folds on my back. It rubs my skin against itself until constellations of tiny skintags form in protest. I look at tintype photos of the distortion of bone and organ caused by Victorian corseting, and I calculate how breathless I could stand to be to force that belly out of sight.

This belly comes from my ancestors. I was never cuddled by skinny, bony mothers or grandmothers. All my people are soft and jolly and restful to exhausted children at the end of a day’s play. That gentle flesh came from Ireland’s oatmeal and Poland’s potatoes. It weathered diet candy chews and scales and low-fat, no-fat endurance tests—this softness is stronger than them all.

My mother never said a kind word about her body in my entire life. When I admired her beauty-queen crown, she told me how her thick ankles almost cost her the prize. When I asked her how she danced to the music she taught me to love, she whispered how a ‘60s shimmy with her young, large, innocent breasts got her kicked out of the YMCA dance. When I told her I thought she was the best secretary in the world, she bemoaned her broad hips and butt, shaped by years of day-in day-out office chairs and Diet Coke.

I was barely five when people started exclaiming how much I looked like my mother. Now when I look in the mirror, I see her body, the one she taught me to despise. And I do.

This belly comes from my survival. I wasn’t small as I grew into adulthood—5’10” by the time I graduated from high school, size 12 in my wedding dress at 21—but I wasn’t terribly big either. The first semester of grad school gave me crushing tension headaches; doctors prescribed an antidepressant that was supposed to help. It helped more than I knew, masking symptoms of oncoming fibromyalgia until the day the medication suddenly, mysteriously stopped working. By that time, I was 75 pounds heavier. The male doctor who prescribed it didn’t think to mention that severe weight gain was common.

Fibro triggered depression; physical and mental anguish became hopelessly tangled. The medication that kept me afloat, active, alive layered fat over my bones. The harder I have tried to be well and happy, the heavier I have grown. I’m told that exercise and getting outdoors more would help my mood, but this belly keeps me from venturing out as much as my pain does. The irony is not lost on me that the medication I take to be happier in my mind makes me unhappier about my body.

This belly comes from my children. One of my midwives told me that babies are very efficient parasites, in and ex utero. She meant to comfort me when I was in month 4 of throwing my guts up 20 hours a day, 7 days a week. I remembered it when my second pregnancy had me sick 24 hours a day for seven and a half months, when I was in the ER for fluids when I couldn’t even keep down water. I only had six weeks to balance a pint of Ben and Jerry’s on the top of my belly, between my breasts, and feel like a proper mother-to-be. I don’t have any of those sideways pregnancy pictures–they didn’t look different enough from my non-pregnancy pictures to be worth taking.

Because I was always tall and heavy, I never had a baby belly that could stop traffic as I crossed the street. Nobody inappropriately rubbed my stomach and asked questions, because none of them could be sure it was pregnancy that stretched my shirts tight. I felt like I needed to be working off my baby weight while I was still pregnant because obesity was on every list of risk factors I was given. And if I couldn’t lose weight when I was throwing up non-stop, losing that baby weight after the boys arrived seemed beyond hopeless.

And my belly comes from food, of course. Bread and tortilla and baguette and pita and bagels. Soup and stew and stroganoff, shawarma and spanakopita. Cheeses: Comté, Cheddar, Delice d’Affinois, Chèvre, Port Salut, Gouda, Midnight Moon, curds so fresh they squeak in my teeth. Pasta, pesto, palak paneer, pho. Dumplings of every gods-given nation on this planet. I adore the craft and kindness of food, its intimate introduction to every kind of culture, the warmest embrace of caretakers everywhere. If I could trade my belly for the world of delicious flavors and spices and surprises, I doubt I’d take the deal.

So this is my belly, and all the things that made it. It’s where I feel things first–anxiety, relief, fear, welling joy. It presses against snuggling children and beloved friends when they accept my preferred forms of greeting and delight. It catches splashes from the pots and pans where I stir up nourishment and comfort for anyone I feed. It hikes up the back of my shirts when I bend down to garden, giving me unexpected sunburns. It rules out pretty dresses and fashionable clothing. It makes me keep the lights off if I want to feel sexy, even alone.

It’s not going anywhere, if I’m going to be honest. I want to believe people who say I’m beautiful like I am. But I don’t know that I’ll ever make peace with this belly. Like so many things about myself, I can’t love it. But it’s undeniably me.

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con.

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con. The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.

The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.

I saw my psychiatrist the other day for my regular check-in. As we went over the list of meds I’m taking, both those prescribed by him and those from other doctors, I said that the anti-depressant I’m on right now is working just fine, and that the only real change since I last saw him was that my pain management docs were having me transition from narcotic pain relievers for my fibromyalgia onto tramadol, a non-narcotic.

I saw my psychiatrist the other day for my regular check-in. As we went over the list of meds I’m taking, both those prescribed by him and those from other doctors, I said that the anti-depressant I’m on right now is working just fine, and that the only real change since I last saw him was that my pain management docs were having me transition from narcotic pain relievers for my fibromyalgia onto tramadol, a non-narcotic.