Social Studies

Social Studies  1 Comment

1 Comment Whose Safety?

CONTENT WARNING: school violence, suicide.

They say more guns in school will protect our children. I’m trying to figure out whose children they mean.

Because it sure isn’t black and brown children. We’ve got a list of names that’s way too long of children who are dead because a cop or an armed white guy thought that their skin color is an existential threat. That weapon can’t be taken off, it can’t be countered by good behavior, and they carry it night and day from the moment they’re born. Black children are almost four times more likely to be shot and killed than white children.

It sure isn’t our mentally ill and disabled children. Teachers are inadequately trained to recognize and deal with mental illness, and most training to deal with neurodivergent or disabled kids trades in misconceptions, ignoring the basic rule that every disabled person should be approached with an assumption of competence.

Mentally ill and disabled students already receive a disproportionate amount of attention from school resource officers—18 percent of disabled secondary students nationwide get suspended, versus 10 percent of the non-disabled students. School staff often read escalating emotions as threatening. My own autistic kid got agitated in a class headed up by a substitute teacher. He was taken down to the ground and handcuffed by the school guard, when a few minutes outside of the room to cool down would have achieved the desired effect.

We also know that children as young as five years old can be suicidally depressed and make attempts to kill themselves, often impulsively. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for youth between ages 5-24. Access to firearms increases the likelihood that a child will attempt suicide; with a gun, they’re much more likely to be successful. In fact, youth are 60 percent more likely to commit suicide with a gun than they were in 2007. How safe are our schools if they increase access to guns for suicidal kids? What kind of horror would it be if “suicide by teacher” became a thing?

And it sure isn’t children who exist where these issues intersect. The majority of US teachers are white women, and implicit bias research shows that, despite training and intention to reach cultural competence, black and brown students are perceived as larger, older, and more aggressive. Add in the unpredictable behavior displayed by mentally ill and disabled students, and the chance of teachers misinterpreting their actions as threatening skyrockets. Disabled students of color are already suspended more often than any other group—1 in 4 for boys, 1 in 5 for girls. Add guns, and the stakes become unbearably high.

In a country where teachers assume the cost of the most basic classroom supplies like books and paper, we’re also increasingly expecting them to lay down their lives in a school shooting scenario. I don’t know a teacher who wouldn’t already do that, to be honest. But in situations where trained, experienced gun users fail to offer a viable defense against a shooter, teachers would be expected to protect the lives of their students as if they were cops or soldiers. That doesn’t even address how law enforcement would react upon entering a school with an active shooter and an array of other people brandishing guns, some of whom could be as young as 22 and of any race or gender.

So again I ask: whose children are safer if we arm teachers? It sure isn’t mine, and it sure isn’t yours.

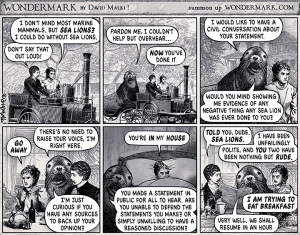

feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.

feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.

TW: suicide, self-harm

TW: suicide, self-harm

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con.

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con. The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.

The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.