Physical Ed

Physical Ed  1 Comment

1 Comment Still Shocking

CONTENT WARNING: physical abuse and torture

On Thursday, April 24, 2014, the FDA held a hearing to decide whether it’s okay to shock autistic people into submission. They held another hearing in 2016. It’s 2018 now, and the shocks haven’t stopped.

The Judge Rotenberg Educational Center In Canton, MA administers strong electrical shocks (60 volts and 15 milliamps) as part of its “aversive therapy” to prevent students from self-harm and aggression, though in reality, records show that they’re applied for as little as blowing spit bubbles or standing up. Children as young as nine years old receive this torture, which Dr. Ivar Lovaas saw as a logical extension of his ABA therapy, which many autistic people already consider a form of torture.

The Center has been subject to a number of scandals, including the deaths of several patients in the 1980s and ‘90s. In June 2012, videotape was released to the media, showing JRC student Andre McCollins being restrained for over seven hours. In that time, he was shocked 31 times for infractions such as “tensing his body and yelling.” JRC spokespeople maintained that it was part of his court-approved treatment plan, but it left him hospitalized in a catatonic state for five and a half weeks. The UN later ruled that the incident fit their definition of torture.

The JRC claims that aversive therapy produces marked behavior modification. They maintain that, “Without the treatment program at JRC, these children and adults would be condemned to lives of pain by self-inflicted mutilation, psychotropic drugs, isolation, restraint and institutionalization—or even death.”

Ultimately, the FDA advisory panel recommended that all of these devices be banned. Some suggested that there should be a six-month period for “tapering off,” as if electric shocks are a medicine from which you must withdraw slowly or experience severe side effects. Even this qualified decision was a narrow one: only 60 percent of the panel approved the ban recommendation.

One of the most disturbing parts of the FDA panel in 2014 was the amount of time spent addressing the question of whether autistic people feel pain the same way as “normal” people. After all, if they can with stand repeated 60-volt shocks—sufficient to inflict second-degree burns to their skin—they can hardly have a “human tolerance.”

At the heart of this whole hearing, and indeed the story of the Judge Rotenberg Education Center, there lies a fundamental question: are autistics really human like the “rest of us”? Othering is a necessary component to any system of training or discipline that requires cruel and inhumane punishment. It’s okay to beat that slave, rape that woman, lock away that crazy person, or exterminate that ethnicity—they’re not the same as us. They don’t even have the same feelings that we have. They’re no better than animals; if we could only train them to be like us, we wouldn’t have to apply such tortures.

And the problem with the dominant rhetoric surrounding autism right now—promoted relentlessly by groups like Autism $peaks—is that the autistic is silent, incapable of communicating from their self-imposed mental prison. An autistic child is a changeling, a dummy replica of the stolen, beloved, “real” child. This heartless thief leaves grieving families in suspended animation, and it must be combatted like anything that would abduct our children.

It stands to reason that anything that might recover a lost child is worth a try. But there’s a fundamental disconnect between the “lost one” and the object on which “therapies” as bizarre and inhumane as bleach enemas, severe emetics, and electrical shocks are applied. The object being treated must stay “other,” or those desperate parents must face the reality that they are physically and mentally torturing their own child.

Except that all of this is a lie. There is no other son, no lost daughter—the children in front of us are real and human. They can communicate, and they can most certainly feel. They will not fare that much better in the world if parents or therapists abuse them until they stop flapping their hands or raising their voices. In fact, they’ll do just as poorly as any physically or mentally abused child. Because that’s what they are when treated with restraints, sensory deprivation, and electrical shocks—victims of torture.

It’s offensive that it took a special hearing in 2014 to decide whether administering shocks to human beings was a legitimate form of “education.” It’s infuriating that the FDA felt the need for more hearings in 2016. And it’s utterly disgusting that in 2018, the patients of the Judge Rotenberg Center are still waiting for the torture to end.

What you can do:

Visit the extensive living archive about the Judge Rotenberg Center, compiled and maintained by Lydia X. Z. Brown.

Take action to urge the FDA to finally enforce the ban they recommended in 2014.

Spread the word using the hashtag #StopTheShock.

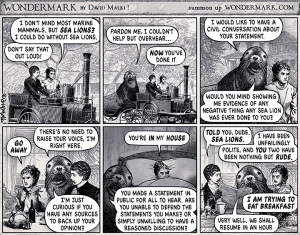

feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.

feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.