Curriculum & Instruction, Psychology

Curriculum & Instruction, Psychology  No Comments

No Comments The Teachers’ Aide

Six years ago, I became a high school teacher aide. I knew how to teach, and I’d had kids who’d benefited greatly from the help of a paraprofessional, as teacher aides are called in America. I figured: I can aid teachers and students, right? How hard could it be?

The answer was, of course, really hard. But also really easy. I just listened to the students when they told me what was difficult, what they wished they could understand or do better, what they felt like in classes and classrooms that didn’t give them everything they needed to succeed. Then I tried to fill in those gaps. It was important to me to not only help the kids learn what they’d missed, but how to weave their own safety nets of self-advocacy and understanding about how they learn differently than their peers.

When I talked to my colleagues, though, they were astounded. How did I figure these things out? How did I know which questions to ask? Most of all, how did I get the kids to tell me these things? It definitely wasn’t because I had any experience with special education. And it wasn’t just that I’m weirdly good at making people feel comfortable. I work hard to be a good listener, and I try to pay attention to the whole person, not just the part that’s talking to me at the moment.

But then I realised: I wasn’t just asking them the questions I thought would get them the help they needed. I was asking them the questions I wish someone had asked me in high school.

I was one of the millions of girls who was never diagnosed as neurodivergent in the 1970s and ‘80s. Autism and ADHD were seen as “boys’ things”, and for a girl to even get assessed, they had to have pretty significant delays or disabling characteristics. The rest of us were just dubbed “sensitive” or “chatty” or “quirky”, or my mother’s particularly cutting compliment, “Jess is intellectually far ahead, but socially backwards.”

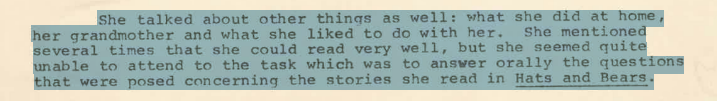

The signs were clearly there, though. When I was finally assessed for ADHD this year, I went looking through the scant documents from my childhood that I have here in New Zealand. Among them was the report from the testing done when it was being decided which grade I should start school in. The researcher’s comments were the purest distillation of “Tell me she’s neurodivergent without saying she’s neurodivergent.”

Who knows what my future would’ve been like if I’d been recognised as autistic and ADHD while I was still in school? Would I have been in so many clubs and activities and advanced courses to satisfy my bottomless need for stimulation, but also be so stressed that I was ill almost constantly? Would I have had my special interests fueled by teachers instead of being told “no more book reports on American history”? Would I have been as vulnerable to relationship abuse if someone had filled in the gaps in my social awareness and emotional intelligence? Would I have finished my Ph.D. with adequate support for my physical and neurological disabilities?

I can’t answer those questions, but I suddenly found myself in a place where I could give a new generation of students the recognition and support that could’ve changed my life. What’s more, I could help other teachers learn how to recognise and support their neurodivergent students, their neurodivergent colleagues, and even themselves if their story mirrored mine. The average teacher may only receive a few hours of instruction about learning differences and neurodivergence—for any more than that, you need to do postgraduate education in special education. That absence of information leaves them poorly equipped to understand how to meet their students’ needs for sensory, socio-emotional, and academic support. And far too many of the kids I was meeting as a teacher aide were telling me things like “You’re the first teacher who’s ever said they can tell I’m smart.” I don’t want to believe that’s the case for a 16-year-old student, but if teachers aren’t being taught to perceive all the forms of invisible intelligence kids have, it seems sadly possible.

I made it my mission to fill in some of the gaps for my colleagues, so I developed my first professional development seminar on how to support neurodivergence in the classroom. Something about the way I explained neurodiversity to my neurotypical colleagues, from the perspective of lived experience but in the language of education they understood, somehow made it accessible and engaging. I was asked to give the presentation for more people, from student teachers to heads of Learning Support departments. I was asked if I had more presentations available, so I made more, focusing on the specific experience of neurodivergent students in the classroom and how simple accommodations could make school less hostile for the kids, their neurotypical peers, and even the teachers themselves. I’d become the Neurotypical Whisperer.

I wasn’t surprised by how many veteran teachers came up to me after my presentations to tell me they’d never learned any of what I’d told them, but I was impressed by how many of them wanted more information. It was the kind of intellectual curiosity and desire for growth you’d hope to find among teachers. We’re in a notoriously time-poor profession, so requests for references and research rabbit holes tell me they thought it was something worth investing in.

The real shock was how many people came up to me after my presentations to say I’d just said what they had desperately needed to hear when they were in school. A lot of these were women, and a lot of them had tears in their eyes as they told me their stories of being overlooked, misunderstood, and often, both underestimated and overestimated at the same time. We talked about the burden of masking: the exhausting practice of creating a physical and social façade that allows neurodivergent people to “pass” in the inhospitable and overwhelming world of neurotypicals. And we talked about the relief of connecting with someone who shared the experience of what it’s like to walk through life feeling so much and understanding so little about the unwritten rules and unmarked roads that neurotypicals seem to follow so easily. I’ve kept in touch with some of those people for years. Some of them have washed out of education, finding the sensory and energy demands overwhelming without wider acceptance of the need to accommodate neurodivergent teachers as well as students. But they still express gratitude for the recognition and acknowledgment they felt as they heard me say they mattered and they had untapped gifts they could offer their students.

I had no idea the title “teacher aide” could mean helping teachers become their whole selves, but it’s a job I’m proud to have had.