My nine-year-old son Connor finishes the partial hospitalization program that saved his life this spring on Friday. He’ll return to school, and his beloved friends and teachers and staff, for the last eleven days of the year. It’ll be a lovely reunion–he’s determined to surprise them on Tuesday–and he’ll get to show off the amazing new self-control and trigger management he’s developed, in a manageable, boundaried time period.

As part of his evaluation and treatment in the program, Connor was tested on a wide battery of skills and scales. Most irritating of these tests was a tear-your-hair-out boring attention test that required TWELVE FULL MINUTES of participation to determine a baseline. We laughed at the irony of his twice quitting an attention test because it bored him, but as soon as he tried it with someone to tell him to keep going, the test revealed no attention span issues.

Connor's first-place winning science fair project this year, about predicting compressive strength of materials based on their atomic structure.

Equally unsurprising to us were the results of his IQ test. He scored 136. Now, officially, there’s no “cutoff” for “genius level” anymore in the updated IQ scoring, but 136 puts him into the 99th Percentile for kids his age. In other words, only one percent of nine-year-olds score higher than that. His vocabulary and reading level is that of a 12th grader. According to a new study, that’s two grades higher than the average of the U.S. Congress.

This kid is staggeringly intelligent. Which comes as news to absolutely no one who’s ever met him. I feel far less proud than affirmed. These scores only quantify the bar that we’ve always felt we have to rise to as his parents. The doctor who evaluated him repeatedly emphasized how unusual Connor’s mind really is–the words “exceptional,” “exceed,” and “excellent” appear frequently throughout the write-up, and he urges several times that Connor receive gifted and talented services.

What did shock us in this evaluation was the statement that immediately followed the quantitative elements: “Connor indicates that he enjoys role-play games, which I would strongly advise against, given how these activities can result in him being more obsessed with fantasy than reality. Connor should be devoting his time and effort to normal activities socially, recreationally, and athletically that would be pursued by a nine-year-old.” Further down, he returns to this point: “Repeatedly, I witness children like Connor becoming consumed with fantasy and role-playing games, derailing their social and emotional development and ignoring ‘normal’ endeavors. The result is a pattern of unusual or atypical interests that ultimately are not shared by their peers, causing them to be viewed as unusual, odd, or atypical and, therefore, contributing to social rejection and emotional alienation.”

My first reaction was, “Holy crap, he thinks geeks are pathetic.”

I saw the Darling Husband’s hackles rise as he read, though he channeled it into humor, since the therapist who gave us the papers wasn’t the one who did the evaluation. Instead, he suggested that they give the doctor a call and tell him what Connor’s dad does for a living.

I saw the Darling Husband’s hackles rise as he read, though he channeled it into humor, since the therapist who gave us the papers wasn’t the one who did the evaluation. Instead, he suggested that they give the doctor a call and tell him what Connor’s dad does for a living.

We shared a laugh at the time, with Connor in the room and unaware of what the papers said, but we were shocked and bothered by the obvious bias in the evaluation, and how utterly dissonant it was with both of our life experiences. How could anyone think such a wonderful hobby was destructive and alienating?

For both of us, fantasy literature and roleplaying games were the ultimate sandbox, an environment finally big enough for the universes our minds could imagine. Sci-fi and fantasy, both in prose and comic books, gave us colorful and expansive vocabularies that challenged us, in the days of stultifying spelling tests and reading assignments that left us cold. Games gave us math problems we wanted to do. They gave us new friends at home and around the world, hours of solo and group entertainment, and eventually, roleplaying games gave us each other. They are our hobby, and our work, and now our legacy to our children.

We understood the doctor’s concern that, if Connor was only into media far beyond his peers’ comprehension, he’d have no common interests with them. But what’s “normal” for a nine-year-old? Chess? No, no chance of obsession there (ahem, paging Bobby Fischer). Baseball? Just what he needs to stay away from unsociable statistics (or not). Guns? That can’t possibly turn out badly. In fact, I’d like someone to tell me what subjects are, in fact, more normal for a nine-year-old American boy in 2012 than heroes, monsters, superheroes, Star Wars, LEGO, and XBox games?

Sure, we’ve known our share of people who couldn’t function well socially in contexts that excluded their primary enthusiasm. Every joke refers to a D&D stat, or a video game plot, or a Monty Python sketch. Every anecdote ties back to a Star Trek episode. And yes, autistic kids get fixated and study the everlasting hell out of what they like. Some days, it’s all they can talk about, and that can be off-putting to other kids who don’t have the sheer bloodyminded endurance they do. But that’s not the vast majority of today’s geeks and gamers, and it’s certainly not Connor.

Connor got a make-your-own sonic screwdriver kit for Christmas. He may have been pleased.

Cam and I will take some credit for keeping his interests wide. Every time he finishes a book, movie, or TV series he’s thoroughly enjoyed, we’ve got three new things racked and ready to suggest. So you liked Star Wars, did you, kid? Here, meet this guy called Indiana Jones. Muppets tickled your fancy? Fantastic–watch this Wallace and Gromit short. Harry Potter and Doctor Who are pretty awesome, aren’t they? Let me tell you about my friends Sherlock Holmes and Lewis Carroll. And the same lack of inhibition that sometimes leads Connor to say tactless or oblivious things allows his passion and enthusiasm for his favorite things to bubble over giddily, and it’s absolutely irresistible. He’s a trendsetter among his peers. They don’t tell him he’s weird for liking what he likes–they want to know what’s got him so excited.

I know the kids around him won’t always be as forgiving of his differences. But the age when that happens was exactly when Cam and I found roleplaying games, and we weren’t alone. Neither will he be. In fact, he’s likely to be in demand as a creative, versatile gamemaster with deft control of rules and narrative, and a bag full of hacks and tricks. Heavens know, he’s learning at the feet of The Master.

We want to let this doctor know that we respect his experience and knowledge, but in this area, he’s got it flat wrong. Games knit society closer together. Connor’s entire existence, and his loving home, come from the power of those stitches. His whole life, since before he was even born, he’s been on the receiving end of love and support from the friends we’ve made through games. He’s already discovered the delight and the challenge in them, and he’s learning social skills in a safe, welcoming environment, in the community of gamers.

How on earth could he grow up healthier without all that?

Literature

Literature  No Comments

No Comments  The first night, I read God Bless the Gargoyles by Dav Pilkey. You can watch it here: Midwinter Tales, 1 Dec 2013(You’ll want to move the video forward to 2:57 where the story starts. I accidentally went live before I finished dinking around with technical stuff.)

The first night, I read God Bless the Gargoyles by Dav Pilkey. You can watch it here: Midwinter Tales, 1 Dec 2013(You’ll want to move the video forward to 2:57 where the story starts. I accidentally went live before I finished dinking around with technical stuff.) The second night, I read I Love You, Little One by Nancy Tafuri. You can watch it here: Midwinter Tales, 2 Dec 2013

The second night, I read I Love You, Little One by Nancy Tafuri. You can watch it here: Midwinter Tales, 2 Dec 2013

tales to the straightforward ones.

tales to the straightforward ones. address that lack of feminine agency, I came up embarrassingly short of good lessons for boys. Current fairytale telling seems to operate on the idea that there’s a finite amount of power and smarts in the story, and if the women get more of it now, it has to happen at the expense of the men.

address that lack of feminine agency, I came up embarrassingly short of good lessons for boys. Current fairytale telling seems to operate on the idea that there’s a finite amount of power and smarts in the story, and if the women get more of it now, it has to happen at the expense of the men. Princess Fiona, Merida, and Rapunzel are smart, feisty, and entirely capable of their own liberation and defense in times of peril. Heroes, on the other hand, like Shrek, Merida’s father Fergus, and Flynn, the hero-rogue in Tangled, are to varying degrees incompetent, gullible, morally weak, and easily distracted from their goals, dependent on the women in their lives to keep them in line and out of trouble. The only male characters that go through real, multi-layered, character evolution in recent years are Beast from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast and Hiccup in How To Train Your Dragon. Jack in the recent Jack the Giant-Killer is a fairly humble live-action hero whose love for the princess, at the very least, does not make him stupid. Shrek does go through some evolution, but seems to stumble his way from lesson to lesson, and seems weakened and henpecked by the end of the series.

Princess Fiona, Merida, and Rapunzel are smart, feisty, and entirely capable of their own liberation and defense in times of peril. Heroes, on the other hand, like Shrek, Merida’s father Fergus, and Flynn, the hero-rogue in Tangled, are to varying degrees incompetent, gullible, morally weak, and easily distracted from their goals, dependent on the women in their lives to keep them in line and out of trouble. The only male characters that go through real, multi-layered, character evolution in recent years are Beast from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast and Hiccup in How To Train Your Dragon. Jack in the recent Jack the Giant-Killer is a fairly humble live-action hero whose love for the princess, at the very least, does not make him stupid. Shrek does go through some evolution, but seems to stumble his way from lesson to lesson, and seems weakened and henpecked by the end of the series. My boys love that these stories are full of adventure and derring-do, and they honestly don’t care too much who’s doing the swashing and the buckling. They’re just as in love with Merida as they were with Shrek. I’m proud of the fact that they don’t see much difference among heroes of different genders. They buck the convention that “you can get a girl to see a boys’ movie, but you can never, not ever, get a boy to watch a girls’ movie.”

My boys love that these stories are full of adventure and derring-do, and they honestly don’t care too much who’s doing the swashing and the buckling. They’re just as in love with Merida as they were with Shrek. I’m proud of the fact that they don’t see much difference among heroes of different genders. They buck the convention that “you can get a girl to see a boys’ movie, but you can never, not ever, get a boy to watch a girls’ movie.” But I wish there were room between the domineering, Johnny-Come-Latelys of Charles Perrault and

But I wish there were room between the domineering, Johnny-Come-Latelys of Charles Perrault and classic Disney, and the updated, apologist buffoons that Hollywood is serving up to boys like mine. They don’t want their fairytales to undergo a gory reversal toward the truly grim versions of Grimm’s. My ten-year-old understood that once parents felt the need to educate their kids that the outside world was a scary, unpredictable place, but when asked if boys still need brutal fairytales to teach that lesson, he replied with a snort, “Are you kidding? All you have to do to learn that is watch the news, for gods’ sakes.”

classic Disney, and the updated, apologist buffoons that Hollywood is serving up to boys like mine. They don’t want their fairytales to undergo a gory reversal toward the truly grim versions of Grimm’s. My ten-year-old understood that once parents felt the need to educate their kids that the outside world was a scary, unpredictable place, but when asked if boys still need brutal fairytales to teach that lesson, he replied with a snort, “Are you kidding? All you have to do to learn that is watch the news, for gods’ sakes.”

But my real sexual education came courtesy of Harlequin. I found a postcard at the library that said, “Get Free Books!” Naturally, I mailed it in, and soon thereafter, six romance novels arrived in the mail. The first one I read was called

But my real sexual education came courtesy of Harlequin. I found a postcard at the library that said, “Get Free Books!” Naturally, I mailed it in, and soon thereafter, six romance novels arrived in the mail. The first one I read was called

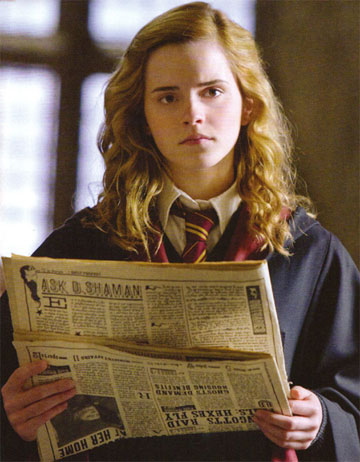

A big part of me is Hermione Granger. I’m a bossy know-it-all witch, always eager to share what I’ve learned with other people. That’s why I’m happiest when I’m teaching–all that reading and study is zero fun if I’m not sharing it with someone else. I’d rather spend my vacation in the restricted section of the library, and I’m a bit befuddled by how little attention most people seem to be paying to, well, everything. I’m pretty sure there’s no problem in the world that can’t be solved with more reading. I’m also fiercely loyal to those I love, and willing to go to the mat (or the troll, or the Shrieking Shack, or the Ministry of Magic) for them.

A big part of me is Hermione Granger. I’m a bossy know-it-all witch, always eager to share what I’ve learned with other people. That’s why I’m happiest when I’m teaching–all that reading and study is zero fun if I’m not sharing it with someone else. I’d rather spend my vacation in the restricted section of the library, and I’m a bit befuddled by how little attention most people seem to be paying to, well, everything. I’m pretty sure there’s no problem in the world that can’t be solved with more reading. I’m also fiercely loyal to those I love, and willing to go to the mat (or the troll, or the Shrieking Shack, or the Ministry of Magic) for them. But Hermione doesn’t cover my weird, unpredictable, impulsive side. For that, I turn to Delirium. She’s one of the Endless, a group of mythic archetypes that function as quasi-divinities/forces of nature in the classic graphic novel series The Sandman. Delirium hasn’t been quite right in the head since her brother Destruction, the big bluff protector of the bunch, split town. She wanders between her own reality and everyone else’s, and is fond of bizarre pronouncements and non sequiturs. At heart, though, she’s a little confused, a lot optimistic, and genuinely loves her family, imperfect though they are.

But Hermione doesn’t cover my weird, unpredictable, impulsive side. For that, I turn to Delirium. She’s one of the Endless, a group of mythic archetypes that function as quasi-divinities/forces of nature in the classic graphic novel series The Sandman. Delirium hasn’t been quite right in the head since her brother Destruction, the big bluff protector of the bunch, split town. She wanders between her own reality and everyone else’s, and is fond of bizarre pronouncements and non sequiturs. At heart, though, she’s a little confused, a lot optimistic, and genuinely loves her family, imperfect though they are.

I saw the Darling Husband’s hackles rise as he read, though he channeled it into humor, since the therapist who gave us the papers wasn’t the one who did the evaluation. Instead, he suggested that they give the doctor a call and tell him

I saw the Darling Husband’s hackles rise as he read, though he channeled it into humor, since the therapist who gave us the papers wasn’t the one who did the evaluation. Instead, he suggested that they give the doctor a call and tell him

Reviewers have widely panned the movie as a “

Reviewers have widely panned the movie as a “