Social Studies

Social Studies  1 Comment

1 Comment Road to Selma: Why I’m Going

Wednesday morning, I leave for Selma, Alabama.

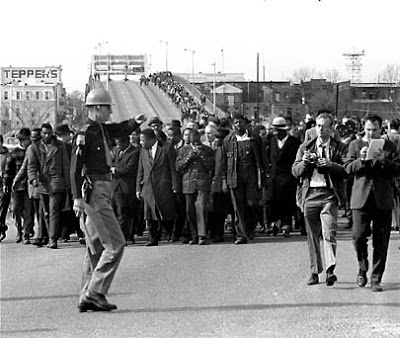

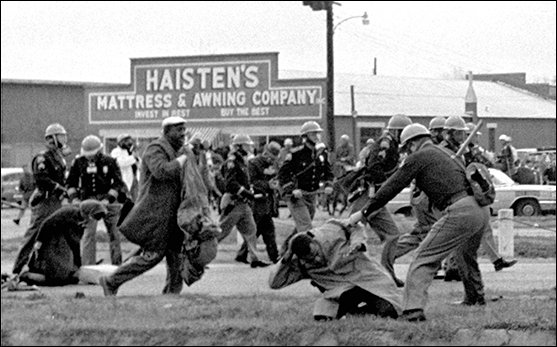

I’ve had this dream for longer than I could remember. I saw grey pictures of its arching bridge in LIFE magazines at my grandparents’ house, magazines that were already old before I was born. The people in their prim, archaic clothes were darker grey than the bridge, darker than the pavement on which they fell when beaten and gassed by racist police.

I didn’t understand why walking would get them beaten. They looked tired and strong and wise and full of grief. And the white people—the people who looked like my family and my neighbors and my teachers—looked enraged. I didn’t understand at all.

35 years later, I’m not sure I understand any better. I still fail to understand why white people treated them with disdain and cruelty and brutal indifference. I fail to understand why white people still treat black people that way.

35 years later, I’m not sure I understand any better. I still fail to understand why white people treated them with disdain and cruelty and brutal indifference. I fail to understand why white people still treat black people that way.

I mean, I know. In my head, I know all the reasons: the history, the psychology, the structural imbalance, the crackpot pseudo-science. And I know it comes down to power. I’ve read, I’ve listened, I’ve studied, I’ve debated, I’ve considered. I’ve even done something close to praying, praying for insight like a lens I never owned.

If I understand anything, it’s why the marchers braved that bridge. I’ve been moved to take up the middle of the street with other people, insisting on being seen, shouting truths that had to be said. I’ve locked arms with people as different from me as possible, yet the same, and refused to be moved until we felt heard.

But I’ve never been as invisible, as endangered, as unvalued as the people in those black-and-white pictures. That’s my privilege.

So why am I compelled to walk in their steps on this fiftieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday? The atmosphere there couldn’t possibly be more different—it’ll be a re-creation of that march in geography only. The road won’t be grooved with the weight of their footsteps, like pilgrimage stairs furrowed by centuries of the faithful. City and state leaders will be there in support. Police will block cars, not bodies. No one will be injured. No one will risk their lives to be there.

But the names of men and women killed by racism are fresh in our mouths today. Explosions and gunshots and dying words ring in our ears right now. Social and economic pressures choke communities of color into slower submission, and still white people refuse to see the oppression that parades in front of us at this very moment.

So, like a white woman named Viola Liuzzo, I ride south to answer the call. Like Unitarian Universalist minister Rev. James Reeb, I go with those of my faith who place justice for the living on the same altar as reverence for the dead. But I’m not a Freedom Rider or any other brave person doing dangerous work. I’m not trying to expiate white liberal guilt. It’s not about me.

I just want to look out from that bridge, through the crowd of strong shoulders, and see the water and trees that stood there 50 years ago. I want to be a witness to the powerful flow of history, and its maddening intransigence. I want to take pictures in full, living color of black and white people marching together to remember, to resolve, to recommit to the necessary work of being fully, fairly human to one another. And I want my grandchildren to see those pictures, and know that I was there.

I cringe as soon as I hear the bell ringing in front of the grocery store. My kids are primed to be generous, and immediately pester me for pocket change to put in the red bucket. I tell them “no” quietly and, to head off the inevitable “why” that follows, say, “They don’t believe they have to help everyone who comes to them in need, and I don’t want to support that.” I fast-walk the boys into the store and give the bellringer a tight smile.

I cringe as soon as I hear the bell ringing in front of the grocery store. My kids are primed to be generous, and immediately pester me for pocket change to put in the red bucket. I tell them “no” quietly and, to head off the inevitable “why” that follows, say, “They don’t believe they have to help everyone who comes to them in need, and I don’t want to support that.” I fast-walk the boys into the store and give the bellringer a tight smile.