Geography, New Zealand Studies, Political Science, Social Studies

Geography, New Zealand Studies, Political Science, Social Studies  No Comments

No Comments On Being Far Away, pt. 2

The first place to experience 12:00 am on January 1st is Kiribati (pronounced “Kiribas”), 19 hours ahead of New York. Samoa and Tonga are next, and then the new year comes to New Zealand. As long as Darling Husband and I lived in the US, we’d call our New Zealand family to wish them a Happy New Year early in the morning on December 31st.

But we had other motives, too. We were also calling for a preview of the new year to make sure it wasn’t kicking off in catastrophic form. This was especially important on December 31, 1999, of course—we needed to make sure planes and banks weren’t crashing because of Y2K. But the stalwart Kiwis were able to reassure an anxious world that the coders and engineers had staved off disaster with their superhuman efforts. Every year, they were like a lighthouse, signaling that it was safe to come forward, at least for the next few hours as we stayed up to watch the ball drop in Times Square.

Now that we live in New Zealand, we’re the ones signaling ahead with Facebook posts saying, “Come on in, the water’s fine!” Of course, we don’t know any better how the new year will turn out—we don’t even know how the rest of January 1st will turn out when we wake up in the morning. But there’s a certain pride in being the one to send that hopeful message back across the time zones to loved ones. I like the thought of manning that lighthouse through the rolling countdown to midnight around the world.

The thing about lighthouses, though, is that they’re stationary, fixed in place. As Anne Lamott says, “Lighthouses don’t go running all over an island looking for boats to save, they just stand there shining.” As hopeful and helpful as they are, they can’t actually rescue anyone directly. And even if they shine as hard as they possibly can, they can’t stop some ships that are moving too fast towards the shoals that will rip them open. They can only stand there, illuminating the horror.

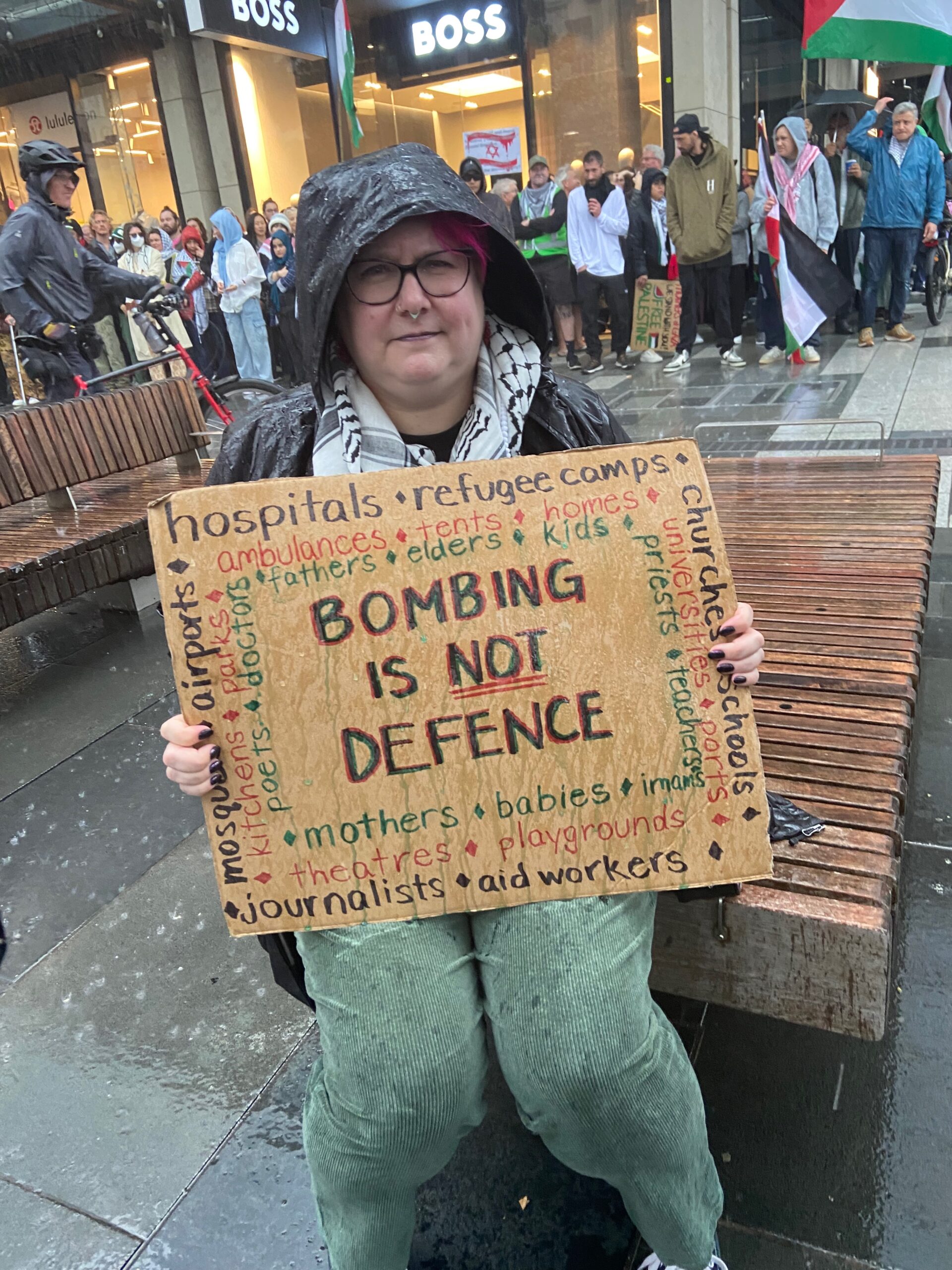

As we prepared to move to New Zealand in late 2018, I grappled constantly with my anxiety about abandoning my activism. I was regularly in the streets with Black Lives Matter Minneapolis and other organizations, usually wearing my neon marshal’s vest. I was interwoven with the wider net of marshals and organizers, all of us looking out for one another as much as we looked out for the protesters within the protective perimeter we upheld. But that net depended on reliable, committed people who showed up. I struggled with the feeling that I was a weak link because of my disabilities. Too often, pain rendered me unable to move and react with the agility and endurance required of someone serving as a marshal. I manned the phone lines with the jail support response team, and I used Signal and Twitter to relay messages. Sometimes, it felt like enough.

Moving away felt like abandoning the net entirely. I wrote about how persistent that feeling has been in part 1 of this series. But when I raised this fear with a good friend in the movement, she had this to say: “Things are probably going to get worse, and folks are gonna need safe places to bug out, with safe people to catch them. You’re not leaving—you’re going to establish a lighthouse.” This gave me the reassurance I needed to leave with a measure of peace.

More importantly, it gave me a way to be useful even at a distance. For years, I’d experienced the always-bizarre phenomenon of meeting complete strangers who’d drawn information or inspiration from my social media posts, making me aware that my reach was far greater than I realized. I knew how to leverage that visibility to boost the signal at home, even from around the world. I learned to work the time difference to my advantage, covering the night shift in America by the light of the New Zealand day.

I’ve also served as a lighthouse in the way my friend described, catching people as they take the leap to our shores. Some of those have been the children of friends who came for study or travel, reassuring their parents that they were in safe hands. But a few have been refugees from the powerful threats faced by today’s America. One friend put me in touch with a mom in Texas who was sending her trans son ahead of her by a few months so he could start nursing school in a place free from the guns and threats brandished at their home every day. For all of these people, we do the same things: pick them up from the airport, feed them, get them a new SIM card, give them a crash course in how to pronounce Maori place names so they can get around. To each of them, I’ve given a pounamu necklace as a token of welcome and blessing from the land where they now stand, one they can take with them wherever they go in the future.

I haven’t caught any of the folks from home yet. They’re still there, in the fight that rages more fiercely than ever. The light I project, searching the waves, picks out their names and faces as they crest on reports from the front lines. But stationary as I am, I can’t reach out and scoop them from the dangerous churn. I don’t know how many of them would actually accept rescue and relief. I struggle not to feel irrational rejection that more of them haven’t come within reach, where I could give them shelter and rest for a time.

All I can do is stand ready and shine as hard as I can, for them and everyone else. If things keep going the way they are, I know more people will need to find safe harbor. I don’t imagine catching people like a superhero, and I neither want nor expect gratitude for it. Long-time activist Brian C. Johnson says in his book The Work Is The Work, “When its light and the boat’s need come together, the boat’s crew lifts up song for the lighthouse. But the crew’s appreciation does not make the lighthouse any brighter.”

The thing that does make my lighthouse brighter is the sense of usefulness and purpose. I know what it is to fling myself into the dark, like a trapeze artist far above the unforgiving ground. Over and over, the spotlight follows them as they let go of the trapeze before the next one has come into view. I’m between trapezes even as I write, waiting to see if I’ll catch or fall. I feel the hot beam of fear and doubt burning me as I wait, suspended and reaching with my whole self.

This world has plenty of spotlights that highlight every motion and risk and mistake, following and searching greedily for the drama of the fall. I’m happier to be a lighthouse whose beacon waits in place to welcome, beckoning with a steady shine.

I’ve continued my activism in new ways down here.

I’ve continued my activism in new ways down here.  But my heart is still divided. If you asked me where “home” is, I’d still have to say America. Watching those friends I love—and so, so many others—fight for the soul of that home is wrenchingly hard. And one of the hardest parts of that is that I’m not there, shoulder to shoulder with them.

But my heart is still divided. If you asked me where “home” is, I’d still have to say America. Watching those friends I love—and so, so many others—fight for the soul of that home is wrenchingly hard. And one of the hardest parts of that is that I’m not there, shoulder to shoulder with them.