New Zealand Studies, Political Science, Social Studies

New Zealand Studies, Political Science, Social Studies  2 Comments

2 Comments On Being Far Away, pt. 1

Activism is in my blood. I’m not sure how it got there—it certainly isn’t genetic. My family has always been more about service, which is good and fine and I’m about it too. I grew up around my grandma and my mom holding church rummage sales, teaching Red Cross swimming and first aid classes, and leading Girl Scout troops. I learned a lot from that, and I gained a healthy appreciation for the warm glow you get from helping others. But that was never enough for me.

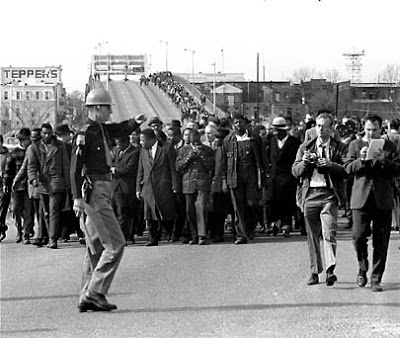

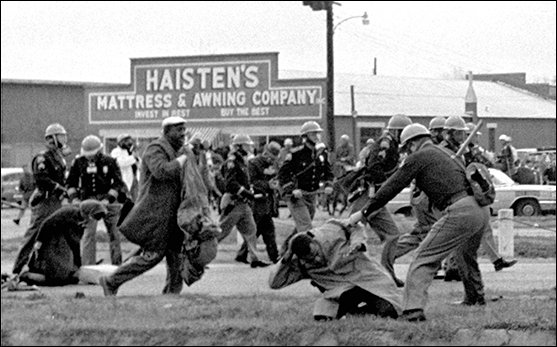

I’ve always been driven to take action when I see something wrong. Every time someone asks me when I started causing trouble (good trouble, as John Lewis called it, I’d like to think), I think of something earlier: “Well, in high school I organized…oh wait, when I was in junior high I went to the city council about…wait, does that thing I did in grade school count?” I’ve since discovered that the activist in me may actually just be the autism in me–neurodivergent people are often characterized by a strong sense of justice and empathy that compels them to challenge unfair systems that harm others. Just think of Greta Thunberg, who often speaks about the connection between her autism and her activism.

I’m no Greta, but I’m proud of my place on the front line of movements that matter to me. Whether it was in the halls of power or the streets, I like to put my body and my voice where showing up matters. And I’ve found the very best people I’ve ever known in those places. That’s not surprising—it’s easy to find friends when it’s a self-selecting group who share your values and passions. And if things get risky, as they sometimes do if you’re challenging authority, there’s probably a fair bit of traumabonding to seal those friendships.

Leaving friends behind was easily the hardest thing about moving to the other side of the world. (Well, leaving so many books behind was hard too, but at least we could pack up some of those and take them along.) I also really struggled with the feeling that I was abandoning my post before the fight was won. I worried that people I respected and cared about would feel that I was quitting the work, that I wasn’t as committed as I said I was.

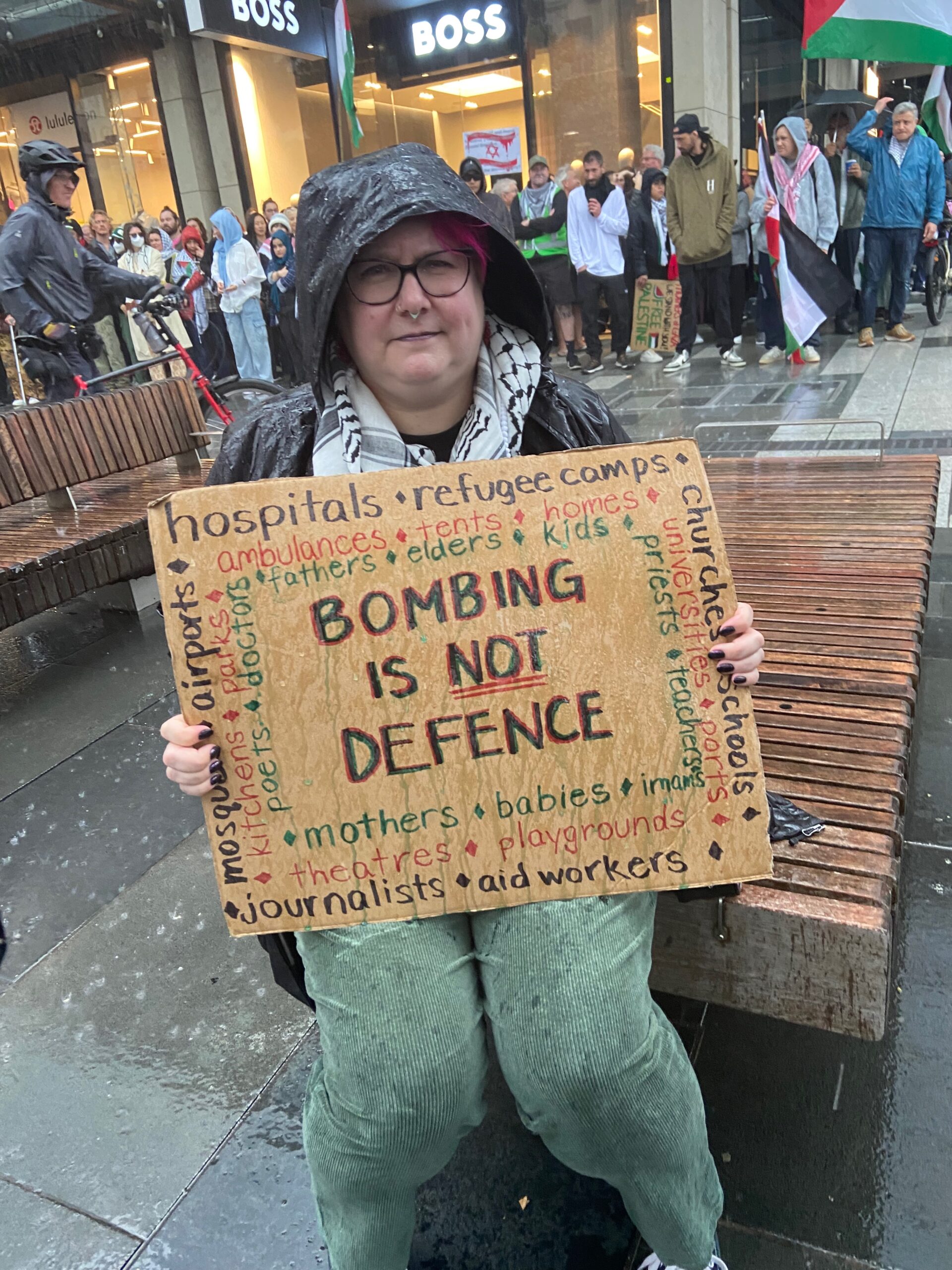

I’ve continued my activism in new ways down here.

I’ve continued my activism in new ways down here.  But my heart is still divided. If you asked me where “home” is, I’d still have to say America. Watching those friends I love—and so, so many others—fight for the soul of that home is wrenchingly hard. And one of the hardest parts of that is that I’m not there, shoulder to shoulder with them.

But my heart is still divided. If you asked me where “home” is, I’d still have to say America. Watching those friends I love—and so, so many others—fight for the soul of that home is wrenchingly hard. And one of the hardest parts of that is that I’m not there, shoulder to shoulder with them.

This has intensified to a painful extent over the last two weeks as ICE invades my home, kidnapping and terrorizing people around Saint Paul and Minneapolis. I know the suburbs and street names in the news reports. I remember the sights and sounds and smells of places like Mercado Central and Karmel Mall. I belong in the pictures of 10,000 people marching down a frosty Lake Street and linking arms in front of the Whipple Federal Building. I want a whistle to warn my neighbors. I feel chants and songs trapped in my throat. I need to be there. I need to fight.

Watching the world from down here has often inspired what feels a lot like survivor’s guilt. For months at the height of the pandemic, we were free of masks and fear—easy enough for a remote island nation of only 5 million people. Even when the disease was running rampant, we weren’t traumatized by numbers of deaths in the tens of thousands, then hundreds of thousands, then over a million. And in the midst of that horror, I witnessed the enraging tragedy of George Floyd’s murder on a street I’d driven hundreds of times. The need to be there, to stand with my community and my activist comrades, kept me up at night like it does now. I went to the solidarity protest here in Auckland because abusive, unaccountable police culture is a global rot. But I didn’t help to shut down a highway or marshal a march, and I felt that inaction in my bones. It was a wrong feeling I couldn’t right.

In a choir, you keep singing to cover others when they need to breathe, just as they keep singing when you breathe. Activism works the same way: others show up when you can’t. There’s no gap when someone leaves—the line is never really broken. That’s been a comfort, but it’s also been an ache. I’m glad there’s no hole where I used to stand, because that would leave the people I care about exposed. But I can’t step up to give them a rest when they need one, no matter how much I want to. Saying “I’m with you in spirit” isn’t too different from offering thoughts and prayers. That’s never going to feel like enough, no matter how much of my heart is behind it.

I need to learn to treat myself like I treat others who have to step back because of circumstance or self-care: with the grace of unconditional forgiveness and appreciation from what they can do with what they have, from where they are at that moment. Here is where I am, and I need to have faith that I’m doing good work and so are they. We’re fighting the same unjust systems on different fronts. And when we win, we’ll meet in the middle and embrace.

aturally, research on the Great War led me to

aturally, research on the Great War led me to