Physical Ed, Psychology

Physical Ed, Psychology  3 Comments

3 Comments Telling Time

This is the third in a series of posts about my recent struggles with mental illness. You can find the first post here, and the second one here.

TW: self-harm, suicide

This is not my actual wrist, or my actual sonic screwdriver, but it IS the watch I wear. I wear mine with the face on my inner wrist.

I started wearing my wristwatch last Thursday. I had to go out and do things, and part of my leaving-the-house routine involves putting on my watch and the two rings I keep looped through the band when they’re not on my fingers. It felt good to slide the heavy cool rings in on my right hand again, to run my thumb over the runes and ocean-grey gemstone.

But I winced as I buckled the watch, because it sits right over the wound on my wrist where I tried to kill myself. I put it on anyway.

It’s not much of a wound, to be honest. I heal very quickly; it’s at the itchy stage now, worse than any of my tattoos were. The only reason there’ll be a scar there is because I was so quiet about it when I got to the hospital that nobody remembered to do anything until I reminded folks hours later, up on the ward. They told me it was too late for butterfly stitches or super glue, and had me wash it well.

Let’s be clear: when I wear my watch over it, it’s because I am ashamed. I am ashamed because it’s a weak wound, messy and shallow, with many individual cuts barely deep enough to break the skin’s surface. It’s humiliating because it looks like I didn’t mean it, like I was only willing to commit enough to draw some blood and get some help. I want to tell people, no, the knife was much duller than I thought, and once I was sitting down with it, with the pictures of my sons in my lap, I was crying too hard and too weak to stand up and find a better blade.

I’m embarrassed that I couldn’t even do that right. I feel like an imposter so much of the time, which is part of what makes it difficult to internalize any of the nice things people say to and about me. The day I tried, I was crushed beneath a thousand failures, things that I see every time I look at myself in the mirror. Those failures are like other cuts, disfiguring me so thoroughly that I can’t understand how anyone could see me and mistake me for a good person. To fail to cut like I meant it just puts more hesitation marks on me, signals that I can’t perform under pressure—a pictograph for despair and incompleteness.

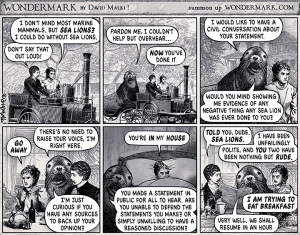

I’m ashamed that I feel confident enough to write about these  feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.

feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.

I’m even ashamed that I didn’t want my parents to find out about any of this. My mom’s not on Facebook, and my siblings unfriended me five years ago, so it’s ironically safe for me to use social media as an outlet and expect it not to get back to any of them. One of the only things I insisted on that numb night I checked into the hospital was, “Don’t tell my mom. Nobody needs that.” The first and last previous time I’d been suicidal enough to go into the hospital, the first words out of my mom’s mouth when she called me there were, “How could you? How could you even think of putting us all through this?” I knew what she meant—I remember the hollow devastation in the days after my grandpa took his life, the questions and no answers. And to be perfectly honest, I just didn’t have it in me this time to sit through that tirade. Guilt was already twisted into every muscle in my body—I couldn’t take any more. But it’s hard to forget that I can’t even do family right when it’s needed most.

With luck, the scar won’t be visible much longer. For months now, I’ve been planning to get a tattoo to remind me to stay alive on the inside of my left arm. It’s the smoothest, palest skin I have, the perfect parchment for a reminder like that. And it shouldn’t be hard for a talented artist like my friend to weave the design around the scar. I like the thought of burying it under something beautiful.

Even then, though, I’m not sure how much longer I’ll be ashamed of that mark. It’s so second-nature to find features and flaws in myself that demand to be concealed so I don’t risk rejection for them. I know some will tell me it’s just the receipt for the price of this precious life. I’m not ready for that yet—I see my belly’s stretch marks that way, but I can’t find what’s redeeming in this piece of evidence yet.

Stigma is related to the word stigmata, the marks on Jesus’ body from his crucifixion. To see and touch them was proof of his identity. This scar translates the stigma of mental illness into that physical evidence, and even covering it with a tattoo or a watch will not erase the judgments it will provoke when others and I will see it. Time will have to tell whether it becomes a symbol of failure or redemption.

You are such a help to me. I see your strength. Strength to show your weaknesses, strength to expose your vulnerability, strength to carry on and learn and grow.

♥

Thank you so much. This is so beautiful, and so are you.