Psychology

Psychology  10 Comments

10 Comments Not Worth The Ink

This’ll be a flash blog post, because I’m flash freaking mad.

I try not to get triggered into red-haze, blinding rage by every awful thing about autism that comes across my Twitter machine. But this was just too much to ignore.

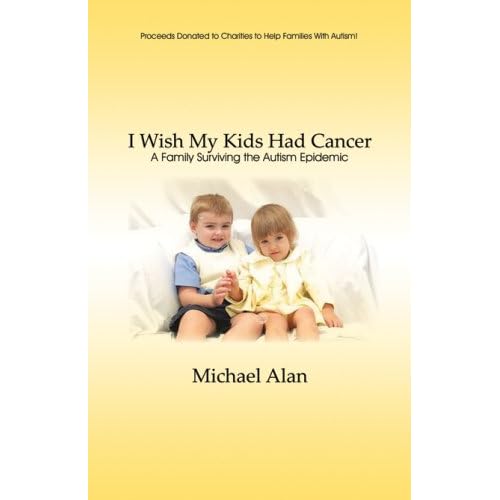

You wish your kids had cancer?! And you’re willing to say that? Not just in the privacy of your own twisted mind, or the quiet of a deep night of self-loathing insomnia, or even to a spouse who might recoil in disgust that you would ever give voice to such a repellent thought, but ON THE COVER OF A GODDAMNED BOOK?!!

Autism is not an illness. It’s not even a disorder–it’s an overabundance of order. Neurodiverse people have difficulty engaging with a world that’s too harsh for their acute senses.

We Are Not Sick.

Autism Is Not A Death Sentence.

But parents like you who hate their autistic children so much, they’d prefer it if they had a devastating disease that requires even more devastating therapies with lifelong effects and increased risks including (most cruelly of all) more cancer, you are a death sentence. Parents like you kill their children because they don’t see the person–they only see the work and therapy and bills and grief. So they push those children under the bathwater and don’t let go. They wrap plastic bags and blankets over the angelic faces of children who are so much more than autistic. Sometimes the parent ends their own lives too, but more often than not, they just shake the Etch-A-Sketch and try to conceive a more “wanted” child who’ll give them the fulfillment of all their dreams.

And your book is going to come up in Google searches. Vulnerable parents, fresh from the shock of diagnosis, will see that title in the results. Some may even buy it from the greedy, vulture-like vanity press that put your despicable words into print. And they will think their child would be better off dead.

You. You did that. To the parent, to the child. You did that.

But you also did one other thing, one you didn’t expect. You made me mad.

See, I’m autistic, and so is my ten-year-old son. We are (and I don’t make such claims lightly) rather amazing. Our memory, our keen senses, our vast imaginations, our complex thought processes, our rapid-fire senses of humor. Our capacity for unconditional love and good work. And we’re friends with other autistics who inspire and motivate and enrich and encourage us every single day.

See, I’m autistic, and so is my ten-year-old son. We are (and I don’t make such claims lightly) rather amazing. Our memory, our keen senses, our vast imaginations, our complex thought processes, our rapid-fire senses of humor. Our capacity for unconditional love and good work. And we’re friends with other autistics who inspire and motivate and enrich and encourage us every single day.

I haven’t given up a single dream for either of my sons, the autistic or the neurotypical. Why should I? They may achieve those goals in unexpected ways, but they can do absolutely anything in the world.

How do I know? Because I have. I’ve graduated, made lasting friendships, participated in government, found and married my one true love, worked toward justice, invented things, created works of beauty, overcome adversity, and mothered two beautiful boys. I’m autistic, and my life is (sometimes uncomfortably) full of meaningful work and relationships.

I’ve been doing a lot of work on health care reform here where I live. In fact, I’ve been testifying at the state capitol about the importance of comprehensive mental health coverage as the state designs the new health care exchanges required by the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare). City Pages published an outstanding article about the fight to enact the Mental Health Parity law Senator Paul Wellstone fought for from 1990 until his tragic plane crash in 2002. Parity means that medical providers and insurance companies will be required to treat mental health by the same standards as physical health. The article is full of horrible examples of discrimination by insurance companies: a woman with an eating disorder was diagnosed to need an inpatient program by four doctors, and her insurance company, United Behavioral Health, rejected her claim nine times for such reasons as “‘There are also religious groups who fast and that is not psychopathology.'” The woman’s lawyer commented, “‘Imagine telling someone with breast cancer to try harder.'”

Mental health parity looks like it’s finally about to happen. If enacted, it’ll help 114 million Americans, but cost less than 1 percent of the total healthcare expenditure under the ACA. When President Clinton enacted parity for federal employees’ health plans, it actually ended up saving the government money. Parity makes good economic, medical, and human sense.

Someday soon, dear author, your autistic kids will be able to get the help they need without a major fight. The only obstacle to them unlocking their full potential will be you. When they get around you–and they WILL get around you–you’ll be the only one left who needs mental help. Won’t you be grateful for good mental health coverage so you can get over your poisonous, miserable ideas about parenting?

At least my mom just wished she’d had an abortion. I can’t imagine how I would feel if I found out she wished I had cancer. I can only hope the children of this egg/sperm donor (because s/he’s not a parent) never see this or, if they do, they are able to realize how much more they mean to people who actually count.

Have you read the book or are you judging it by its cover?

You’re correct in your assumption–I have not read this book. Despite the well-known adage, I feel justified in making certain assumptions from that cover, though. First, I understand the value of a provocative title, but this one is so far beyond the pale. Why not say, “I wish my children had the flu” or “I wish I could cure my children’s autism”? The same message is conveyed without making the connection to something so intrinsically painful and extreme.

Second, the subtitle refers to the “autism epidemic.” While that phrase gets thrown around a lot in the mainstream media, there’s a subset of writing about autism that focuses on the rising number of diagnoses as if autism were something new and (in many cases) stemming from some environmental cause(s). It’s also very common for that kind of book to focus on the experience of parents, rather than the children (usually because it’s thought that non-verbal kids are incapable of higher thought or communication, which is patently false), and often contains passionate wishes for a “cure.” I often refer to these books as the “Autism Speaks library,” since that kind of thinking is typical of that organization’s messaging and mission.

I urge folks who’ve only encountered the body of work searching for causes and cures of autism to expand their reading into the growing field of writing about autism by autistics. “Look Me In The Eye” by John Elder Robison and “The Journal of Best Practices” by David Finch are some of the more popular books of this type, and the “Loud Hands: Autistic People, Speaking” anthology is revelatory in its scope of inclusion.

“As horrible as it sounds, sometimes I wish my kids had an incurable condition I could understand and come to terms with easier” wouldn’t fit on the cover.

I insist on hope for the children of this author, because parents are not the only influence. Sometimes it is the kindness of other adults who turn a child’s landscape into a positive place to be. I hope these children have such influences in their lives and that, one day, they can look back and recognize, with compassion and clarity, who meant what for who they have grown up to be.

Kids are smart and they do figure things out. In some ways, that is the worst, harshest justice a parent can face.

Several hours cooler, I appreciate your view, and agree with it to a certain extent. Kids *are* smart, and they do figure these things out at a surprisingly early age. My concern is that, if a parent is so fixated on discovering a fix for their children, they treat them as if they’re “less than” and are far less likely to advocate strongly the way parents of autistics often have to to get the necessary services and respect their kids need and deserve. I worry for the kids whose parents can’t accept the children they received, and the valuable time lost in their development.

Wow.Great job. I thought I had heard every negative parent comment.This is unbelievable.

This book title pisses me off for more than one reason.

I’m autistic who was diagnosed as an adult. Yet, there is evidence I had a diagnosis much sooner. When I was five, mostly non verbal but could read and could write in more than one language at fourth grade level, my pediatrician suspected I might have autism. He dismissed his diagnosis on the basis that I was a girl. In 1973, most doctors were misinformed and thought autism was exclusive to boys.

My son is autistic and a big challenge because he’s PDD-NOS. He’s mine and I don’t care how many problems he has. Both he and I adjust.

I also hate this because I grew up in Southern California. Though my family moved around a lot, most often we would end up living with my grandmother. Her house sat across the street from a small private airport for crop dusters. As many people my age know, up until the mid 1970’s DDT was the main bug killer the crop dusters used on the food.

I grew up with kids born with cancer. Several kids that lived near that airport got some sort of cancer or had some sort of birth defect. I include myself in the birth defect category because the problem with my reproductive system was cause by the exposure.

I would not wish anyone to go through what I saw my friends who did have cancer had to go through day to day.

I know it was worse for the parent dealing with chemo and such.

This person is a moron who doesn’t know anything.

I felt compelled to comment because it’s pretty rare that I have enough expertise to feel confident talking to strangers.

My miracle daughter Genevieve Celeste, tested out with autistic spectrum “disorders” at 2 and a half.

And she was diagnosed with leukemia (A.L.L.) at 3.

So, I got to witness the whole package. Frankly, it’s somewhat difficult to sort out the various symptoms, after-effects, follow-up conditions and traits from each other. Her mother and I, thank God, never had a realistic chance to wish that one was the other. But we are agreed: our daughter is a miracle and we have been very blessed in our lives.

One important impact of the combination- Genna was only speaking in monosyllables, and only to us, before the cancer (though she could READ from around 18 months onward, which fooled us about her condition). When the cancer struck and she was in hospital for weeks at a stretch, all her verbal communication disappeared for at least a year (she was down to “no” and “OK”). No speech worth noting until nearly six years old. So it’s a tough slap to have to face.

But today- she’ll be 16 in April. She studies languages (the rote memory!) and acts onstage (can’t keep her away), plays the flute, sings, in short she thrives. And while the cancer gave her lingering and serious side-effects, the cure of it was almost routine. ALL has a 85%+ cure rate now; the doctors were very confident with us (also a great local hospital). The autistic traits, by comparison, have largely mainstreamed but are still quite noticeable to anyone who spends more than a minute with her. Only her mother, really, can teach her well.

So on many levels, it’s a complex comparison. All the best to everyone who reads this.

Thank you SO MUCH for sharing that story. It’s truly amazing, and I’m so glad you all came through it with your hope and joy intact. I excelled in languages and music too, in large part because of traits I now recognize as autistic, and I’m sure she gets as much happiness from those pursuits as I do even still. Obviously I don’t know much about your situation, but if I were in an environment for a long time that’s as noisy, invasive, and changeable as a hospital, I’d probably regress to barely verbal too, just to cope. I was in for a week last year with pancreatitis and gallbladder surgery, and I wasn’t very cooperative about it at points.