Ancient History

Ancient History  3 Comments

3 Comments A Drop of the Irish

I’m five-eighths Irish, and it shows in all kinds of ways. I don’t tan–I just burn badly, then peel back to freshly-drowned white. My complexion also blushes impressively at the first whiff of emotion or alcohol. I’ve got a decisive jaw and a stubborn chin, and the attitude to back them up. I look damn fine in any and every shade of green. I’m hard-pressed to keep my toes still if there’s a spirited jig or reel playing. I’ve got a mighty temper, which rises and falls with sometimes alarming speed and whimsy. And I’ll take a chilly, misty, drizzly day–a “soft day,” to the Irish–over a cloudless 80-degree one hands down.

And oh yes: a significant number of my relatives are alcoholics.

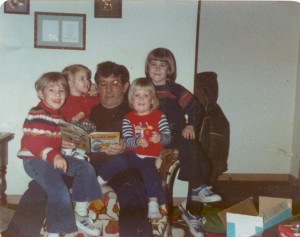

My Grandpa Boyle, mobbed by the grandkids as usual. I'm top right; my sister lower right; 2 of many cousins on the left. Salt of the earth, my grandpa was.

Now don’t go getting on me for pandering to an ethnic stereotype. Not all Irish are drunks, probably not even a majority. But Irish social interactions have been lubricated by smoky whiskeys and beers as thick and dark as the new moon since time immemorial. (Don’t question me when use idioms like “time immemorial;” I’ve literally read the very earliest Irish historical documents.) And for so many people with Irish blood in their veins, it’s an understatement to say their relationship with alcohol is fraught with generations of experience and emotion.

And so it was with my paternal family. I’m descended from the Boyle clan, with a side order of Higgins, and I grew up in and near Milwaukee, home of the most epically huge and enthusiastic Irish Fest in North America. Holidays, christenings, birthdays, marriages, funerals, and occasional random weekends were spent in the wood-panelled basement of my grandparents’ home in a blue-collar suburb. (If you don’t know about the Irish and wood panelling, you need to pay more attention to Denis Leary.) On every available surface, there were either food or bottles of booze; with both, quantity over quality was the byword. Both were consumed at a steady pace, with the grit and determination of long-distance runners.

What I remember most about those parties–besides my cousins and slipping around on the tiled floor in my fancy shoes–was the volatility. The growing volume level, the slightly unbalanced quality to the adults’ laughter, and the overbroad, unmeasured gestures. The sudden snap of a frayed temper, the crack of an angry outburst. The atmosphere of precariously balanced danger. The longer the nights drew on, the more I instinctively shrank into myself, made myself smaller, so I wouldn’t upset the equilibrium.

If it had only been at these parties, I’d probably be writing about this with more humor. But it was at home too, with no parties, no gaiety–just a staggering, slurring father, present in so many snapshots of my childhood. He worked hard, but there were weeknights he came home so hammered, he was still drunk when he walked out the front door the following morning. He’s a big man, 6 foot 4, and thickly built. Sometimes, he came home in the mood to play, but he couldn’t control his strength when he was drunk, and his horseplay often left at least one of us kids crying. Most nights though, if he didn’t just stumble into bed, he was angry and belligerent. I’m the oldest of us three siblings, so I felt it was my responsibility to protect us. We spent nervous hours crouched in the bathtub; the bathroom was the only door in the house with a lock.

I was a pretty precocious kid, so when my mom finally demanded that he leave when I was about 8 years old, I was all for it. The next two years were hard, really hard, as my mom worked to support us on just her secretary’s salary–I shudder to think of what it would’ve been like if her parents hadn’t lived a mile away and been so generous with their time and resources. She knew the man who would become our stepdad from church–he was the Minister of Music, and she sang in the choir. She knew he’d been raised a teetotaler. Sure, he was 20 years older than her, but he’s a good man, and she knew he’d take better care of us all.

The rest of the Boyles knew my mom had given my father chance after chance after chance, but he refused to admit he had a problem, and they blamed the breakup on him. We’ve maintained very good relations with them all along, even after my father decided it was easier to think of us as dead for a while there. They supplied us with pictures of our new half-brothers from his second marriage, and they sent representatives to important events, like graduations and my wedding. I saw my father at a family reunion when I was 17. We hadn’t spoken for 8 years at that point; we wouldn’t speak again for another 17 after that.

My personal reaction to the alcoholism I saw rampant in that branch of the family tree was unusual, I guess. I decided as a child that I would never even taste alcohol until I was old enough to be sure that my personality was fully formed, and that it didn’t have addictive tendencies. Lots of my friends didn’t understand my adamant refusal to drink in a small town where drinking, having sex, and renting movies were the primary forms of entertainment, often performed in combination. But I’ve been fortunate to have a happy assortment of offbeat friends who took that quirk in stride.

I went to France my senior year of college–I would turn 21 while I was over there–and I went with the attitude that, if the occasion rose and I felt comfortable, I’d try a drink that year. But I wasn’t ready when I first got there, and the French college students just shrugged off my refusal of beer-based hospitality, and pointed me to the Coca-Cola. The real problem was with the French adults. “BWAH?!?!?” they would exclaim. “But you are in France! Everyone drinks in France! You can’t not have wine!”

Oops. Magic word: can’t. See, I’ve got this anti-authoritarian button that pops out when someone tells me I can’t, and it sounds like this: “Oh, I can’t, can I? Well, that cinches it. Just watch me.” And I didn’t drink the entire year–not on my birthday, not at any of the outrageously good meals, not in any of the charming cafés or brasseries, even though my hot chocolates and Cokes cost me 12 francs, and a beer would’ve cost me 7. That’s some fine Irish stubbornness for you there.

I had my first drink of alcohol on my wedding night, a champagne toast with my friends. The friends who’d been with me all through college and the year in France couldn’t stop exclaiming how mind-bendingly odd it was to see me drink. Some knew why I’d waited; they were happiest to see me let go of that shackle. Funnily enough, because I’d waited until I was a fully grown adult to start drinking, I’ve never been drunk. Between my Irish/German constitution, my plus-size physique, and my unwillingness to drink any alcoholic crap that comes along, getting me drunk is a damned expensive proposition, and I’d so much rather spend that money on books.

I reconnected with my father when we moved back to Wisconsin for a few years. I’m the mother of his only two biological grandchildren, and I felt it would be stingy and petty of me not to let him get to know them, and them him. He hasn’t aged particularly well, but when he grows out his beard and hair, he looks like a rather jolly Irish Santa. They send us gift cards at Christmas; I send them cards and drawings from the boys. I don’t like to think how I would’ve turned out if my mom hadn’t had the steel in her spine to leave him, and when it’s time to talk to my boys about drinking and drugs, I’ll tell them what my first 8 years were like, and why I’ve made the choices I have.

Family and history–they’re the most Irish things I have to share with them.

But every once in a while, especially when I see something of myself or Cam reflected back from them in flawless mirror image, my mind flits across whimsical images. Sometimes, it’s the three fairies from Sleeping Beauty, hovering over their cradles and bestowing gifts. And sometimes, more magical in its own way for being true, I imagine those tiny coded zippers–unfurling, melding pieces of each of us into someone new and unique but so familiar, then coiling again, before doing a little do-si-do and starting the whole thing over again, in the blink of an eye. Amazing, but frankly, it hurts my head a little to contemplate it all.

But every once in a while, especially when I see something of myself or Cam reflected back from them in flawless mirror image, my mind flits across whimsical images. Sometimes, it’s the three fairies from Sleeping Beauty, hovering over their cradles and bestowing gifts. And sometimes, more magical in its own way for being true, I imagine those tiny coded zippers–unfurling, melding pieces of each of us into someone new and unique but so familiar, then coiling again, before doing a little do-si-do and starting the whole thing over again, in the blink of an eye. Amazing, but frankly, it hurts my head a little to contemplate it all.

This has been a weird month for our family. While we’re overjoyed at the release of

This has been a weird month for our family. While we’re overjoyed at the release of  Guilt is a normal state of existence for mothers everywhere, but seeing the depression that’s derailed whole seasons of my life wrap its sticky, persistent black tendrils around my beautiful boy–it weighs like a stone on my heart. And it’s probably no consolation to him, when he says there isn’t anything good in the world for him, or anything good he can give back to the world, that I can look him straight in the eye and say, “I know exactly how you feel right now.” Sometimes, I do things that fly in the face of my own experience–I don’t particularly like or find comfort in being touched when I’m that depressed, but I hold him so tightly as he weathers hurricanes of emotion too big for his little body, and I hope it brings him calm sooner than he would find alone.

Guilt is a normal state of existence for mothers everywhere, but seeing the depression that’s derailed whole seasons of my life wrap its sticky, persistent black tendrils around my beautiful boy–it weighs like a stone on my heart. And it’s probably no consolation to him, when he says there isn’t anything good in the world for him, or anything good he can give back to the world, that I can look him straight in the eye and say, “I know exactly how you feel right now.” Sometimes, I do things that fly in the face of my own experience–I don’t particularly like or find comfort in being touched when I’m that depressed, but I hold him so tightly as he weathers hurricanes of emotion too big for his little body, and I hope it brings him calm sooner than he would find alone.