Social Studies

Social Studies  No Comments

No Comments Scouting at the Shutdown

While the Boy Scouts Movement has creepy, eugenicist, imperialist, moderately fascist origins, the Girl Scouts have no such conflict attached. The values of community, commonality, friendship, and service pervade the Girl Scouts’ ethos, along with a focus on developing practical skills to make girls feel strong and self-sufficient. Even that most dangerous of developments—the Girl Scout cookie—fosters an entrepreneurial spirit in its purveyors.

I grew up steeped in Girl Scout values, even if I dropped out when I was only a Junior Scout. I never made it to one of the international Girl Scout/Girl Guide lodges in foreign countries that I dreamt of as a kid already obsessed with other cultures and travel. But my grandma and my mom were both long-time Girl Scout troop leaders, and even if I didn’t get a badge sewn on my sash for them, so many of the skills they taught me came from that curriculum of skills and values.

I learned to sew, cook, camp, and navigate in nature from both of my mother’s parents. Whether it was a trip to the North Woods of Wisconsin or a weeklong wagon train adventure in the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park, a lot of my memories of them involve forests, campfires, and practical problemsolving. Whenever I see birch trees, or smell pinewood smoke, or rub apart the silky seeds of a milkweed plant to give them a boost in spreading, I feel their steady presence around me.

I became involved with the occupation of the Minneapolis Police Department 4th Precinct following the police killing of Jamar Clark. Of course you did, you may be saying—where else would I be in these years of racial justice work? I was there, marshaling, the first night, when the crowd marched between the 4th Precinct and the Minneapolis Urban League to call out and disrupt the mayor and police chief who were offering the same unsatisfactory rhetoric of moderation that Dr. King skewered in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail. I was there, chant-leading for 3.5 hours without a bullhorn in the pouring rain, and later holding down the west gate as witnesses and allies pressed large tarps to the chainlink fence to protect themselves from the pepper spray the cops deployed.

But I was there, too, on the peaceful days. On a rainy Tuesday afternoon when we sat under the covered entryway and formed a sewing and knitting circle that reminded me of the old “Ladies’ Sewing Circle and Terrorist Society” buttons (though, times and trolls demand that I say that the only people acting in a terroristic way at the 4th Precinct have been the cops themselves). On a chilly Friday night when we gathered, a thousand strong, for a candlelight vigil demanding justice and transparency. On the next Sunday night, while people of color from the Northside met elsewhere to plan next steps, with my boys along so they could say they saw this all someday.

But I was there, too, on the peaceful days. On a rainy Tuesday afternoon when we sat under the covered entryway and formed a sewing and knitting circle that reminded me of the old “Ladies’ Sewing Circle and Terrorist Society” buttons (though, times and trolls demand that I say that the only people acting in a terroristic way at the 4th Precinct have been the cops themselves). On a chilly Friday night when we gathered, a thousand strong, for a candlelight vigil demanding justice and transparency. On the next Sunday night, while people of color from the Northside met elsewhere to plan next steps, with my boys along so they could say they saw this all someday.

The encampment has reminded me of my grandparents and my Girl Scout origins so powerfully, it’s given me sensory flashbacks at times. I’ve told stories around pinewood fires that smoke and spit. I’ve sung songs in wide circles of shared strength and faith. I’ve hugged strangers, and taught skills (some I wish I didn’t have to, like how to safely wash eyes stung by tear gas), and eaten food cooked with love for a crowd. Every picture of a red, crackling fire and nylon tent takes me back to my childhood.

Other things have added new associations to my memories of camping and community. When the music starts up, people dance, old and young. When it’s time to link arms and chant, we don’t choose the neighbors on either side—we just form an unbreakable, committed chain of bodies and voices. When we need supplies of one kind or another, we post Google Docs, tweets, Facebook posts, and group texts. When comfort and consolation are called for, people drive up in cars with heaters and warm seats and sometimes even kittens to cuddle.

This encampment obviously isn’t infinitely sustainable—winter is coming, as Ned Stark would say. But that doesn’t mean it was pointless or ineffective. It has radically changed the narrative of what the North Minneapolis community can do, among people who don’t already know: serve one another, sustain a peace among rivals, clean and feed and provide for people of every age and background. These things take work and discipline civic-mindedness and good faith, things that the narrative of white supremacy says are beyond the ability of communities of color. They can defend themselves in the face of gross brutality, as we saw repeatedly throughout the week. They can build intersectional relationships, with groups as diverse as the Sierra Club and labor unions, that will pay dividends in the future as we work toward the combined goals of racial justice, economic justice, and environmental justice.

I’d like to think that the founder of the Girl Scouts, Juliette Gordon Low, would’ve approved of the 4th Precinct Shutdown. I’d like to imagine that current and former Girl Scouts lace the crowds that have gathered to defend the prolonged protest. I’d like to know that the communal sharing has spread skills and gifts in a way that will serve the Northside residents and others for years to come. And I’d like to believe that, in the seasons to come, the smell of woodsmoke and the feel of yarn and the sight of tents and the greetings of new and old friends will remind everyone of what the uncommon, beloved community we built together at the 4th Precinct.

aturally, research on the Great War led me to

aturally, research on the Great War led me to

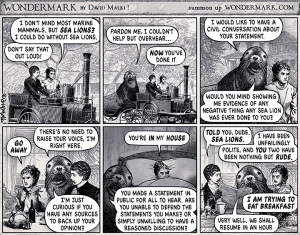

feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.

feelings so openly here, but I’m mostly unwilling to have a conversation about this in person. Even with good friends, I’d rather the mark was out of sight so we can talk more abstractly about my problems. The wound is the very opposite of abstract; it is hopelessness in a concrete, raised mark. When I don’t want to have those conversations in real life, I feel like as much a fraud as some sea lion (see adjacent comic) flopping around online, splattering his abusive comments all over everyone’s internet when he barely has the guts to say hi to his neighbor if they collide on the street. I’m just another fake getting virtual courage behind a computer screen.

TW: suicide, self-harm

TW: suicide, self-harm