Photo by Amit Erez/iStockphoto.com

Hanukkah has a gloss on it, a festival of light like others this time of year. Part of that gloss has developed in proximity to the flash and dazzle of Christmas, but before that, much of Hanukkah’s attraction was the chance to delight children with candles, dreidels, chocolate, and wonderful practical gifts like socks and pencils.

But another aspect of that gloss comes from the effort to avoid examining the complex origins of the holiday. It’s what comes before the miracle of the oil in the Temple that spurs on such frantically cheerful celebration. The destruction of the Temple that made its rededication necessary followed a bitter civil war within the Jewish community. Jews who wanted to keep Jewish culture pure and separate fought against Jews who wanted to give up some of their Jewishness to join the dominant Greek culture that seemed like the flagship of progress and prosperity.

When Jerusalem was annexed by the Seleucid rulers of the eastern Greek kings, the Greeks and their Hellenized Jewish followers desecrated Jewish holy sites, killed fellow Jews, and forced others to break the laws of the Torah by eating pork or getting “uncircumcised,” a process about which I wish to know nothing at all, since circumcision itself is a removal of skin. Many Jews died rather than submit to these rituals, but many others submitted in hopes of assimilation into the wider Hellenic society where opportunity lay.

This conflict, and the uprising by the Maccabees that delivered two decisive military defeats to the forces of Antiochus and drove Greek troops from Jerusalem, are filled with questions we’re still struggling with today: “How does a community maintain its identity in relation to the broader culture? How much should outside influences be resisted, and how much embraced? How much do we depend upon God to save us and how much upon ourselves?” (1)

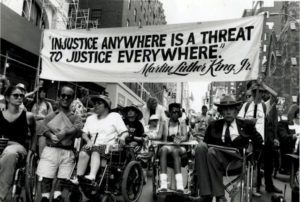

I see these themes playing out in a different context recently, that of the Black Lives Matter movement. Black Lives Matter seeks to empower black communities and individuals after 400 years of dehumanization and systemic racism. There’s an effort to lift up and honor the ways black culture is unique, and value its resilient manifestations in a society that constantly seeks to dominate it through force and privilege.

As with the Maccabees, this is a fight that springs not only out of the oppression imposed by the state, but also in opposition to the forces of assimilation, respectability, and appeasement from others in the community who see success and respect in the dominant culture as the only way to get ahead in society and avoid punishment by the state. This was cause for civil war among the Jews, and the conflicts between parts of the black community over the strategy for freedom can become nearly as heated.

These complicated issues of resistance, solidarity, and freedom have been on my mind for weeks now, during and following the occupation of the 4th Police Precinct in North Minneapolis. It followed yet another incident of state violence, the police killing of Jamar Clark, a 24-year-old black man. Instead of just marching once or twice in symbolic protest, then burying the injustice with the victim, leaders from Black Lives Matter Minneapolis, Black Liberation Project, and the Minneapolis NAACP decided on a strategy of resistance to raise tensions in an effort to procure justice: a Federal investigation of the murder, the release of the names of the two officers involved, and the public release of the video surveillance tapes from a variety of angles around the crime scene.

Tents sprang up, then food service, then winter clothing giveaways. Sisters Camelot pulled their bus right into the camp and unloaded hundreds of pounds of fresh produce over the days of the occupation, most of it flowing out into the community. Some days, the lines of cars stretched for over a block, each one pulling up to donate firewood and propane to keep protesters warm day and night.

Photo by Jeff Wheeler/Star Tribune via AP

For eighteen days, campfires burned in a line down one block of Plymouth Avenue. They were carefully tended: logs laid in careful formation, coals stoked to a new blaze, water and sand at the ready nearby, ashes diligently swept away. The miracle of this string of lights wasn’t the fuel needed to keep those fires burning; it was the community that formed to keep the whole occupation bright and steadfast. Just like Hanukkah, there were stories and games and songs and food to push back the cold darkness of racism and defeat. Hanukkah means dedication, and that’s what kept the 4th Precinct Shutdown going: dedication to the neighborhood, dedication to the people, dedication to the idea of freedom and equality.

In the wake of the city’s destruction of the camp, Minneapolis police cars are pulling people over, trailing them far beyond their jurisdiction, just for having shown up on that battleground. Police retribution is a real fear for Northside residents, and efforts to procure a promise against retaliation and continued police violence have been met with silence. This form of oppression resembles the German tactic of “collective responsibility” in the face of resistance. “This retaliation tactic held entire families and communities responsible for individual acts of armed and unarmed resistance. The fact that thousands did fight back is remarkable.” (2)

If the lights of Hanukkah are meant to give hope, so were the lights on Plymouth Avenue. And if the resistance of the Maccabees is meant to inspire us to band together in the face of oppression, so was the 4th Precinct Shutdown. And if lighting other candles from the Shamash is meant to give us courage to be the kindling light in others’ lives, Black Lives Matter calls on us all to be the beacons that shine love and light into the shadows of our society and make it better.

Photo by Jeff Wheeler/Star Tribune.

“Chanukah, 5692.

‘Judea dies’, thus says the banner.

‘Judea will live forever’, thus respond the lights.”

— Rachel Posner, Nazi Germany, 1933. (3)

Earth Sciences, New Zealand Studies, Uncategorized

Earth Sciences, New Zealand Studies, Uncategorized  No Comments

No Comments

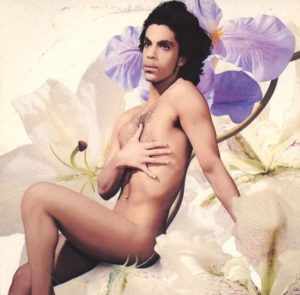

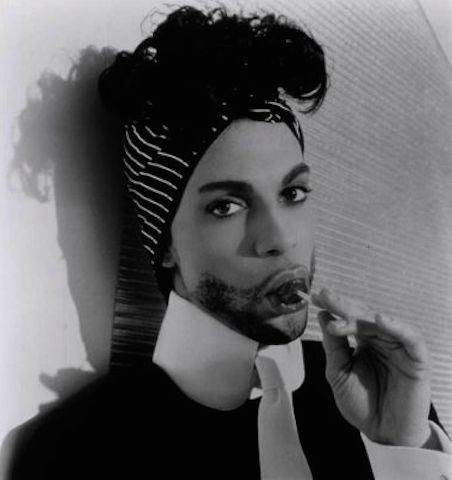

Prince was queer before I knew what it was. I sang along quite innocently as he breathed, “I’m not a woman, I’m not a man, I am something you can never understand.” And to be honest, I didn’t question it. His whole self was confirmation of that statement. My autistic perseveration as a child was history, and I especially enjoyed historical fashion. Prince was a museum of styles on parade. He had it all: Marie Antoinette’s beauty mark, Cleopatra’s kohl liner, Lord Byron’s carelessly tumbling curls, Cab Calloway’s finger waves, George III’s frothy lace jabot. Prince displayed a fearless feast of gendered signifiers, embracing and rejecting them all at the same time, sparing no one the intense focus of his seduction.

Prince was queer before I knew what it was. I sang along quite innocently as he breathed, “I’m not a woman, I’m not a man, I am something you can never understand.” And to be honest, I didn’t question it. His whole self was confirmation of that statement. My autistic perseveration as a child was history, and I especially enjoyed historical fashion. Prince was a museum of styles on parade. He had it all: Marie Antoinette’s beauty mark, Cleopatra’s kohl liner, Lord Byron’s carelessly tumbling curls, Cab Calloway’s finger waves, George III’s frothy lace jabot. Prince displayed a fearless feast of gendered signifiers, embracing and rejecting them all at the same time, sparing no one the intense focus of his seduction.