Uncategorized

Uncategorized  No Comments

No Comments Relics of a Well-Spent Life

In a massive storm on the Eastern Seaboard in the 1800s, the deadliest and most destructive until Hurricane Sandy hit last year, residents of one seaside community reported watching one house lifted right off its foundations by the storm surge. The house then sailed back out on the waves, fully intact and upright, until it crossed out of sight on the horizon. It was never seen again, but the owner (so the story goes) found precisely one china plate from her mother’s heirloom set in the sand two miles down the beach in the days after the storm.

It’s very trendy to say that one could really do without every thing they own. We downsize, we donate, we do with less, and we feel very virtuous about it. “Stuff just weighs you down,” we say, and we’re not wrong. Objects are attachments that keep us from being fully mobile, fully free.

I’d be lying if I said I’d never contemplated a merry blaze as I cleaned up one more piece of homework, one more sock, one more crayon. We have things in a storage unit back in Wisconsin that we haven’t seen since we moved almost three years ago, and I can’t honestly say I’ve missed many of them. And there’s certainly more in this apartment than we truly need; the difficulty actually comes with disposing of much of it–where can it go, if recycling isn’t possible when reducing, but contributing stuffed animals and kitchen implements to a landfill?

I’ve even trained myself out of several things I thought I could never do without. I used to answer the “What would you save in a fire?” question quickly: “My photos.” Never mind that they took up four heavy crates, I had plans as early as high school for how to throw them out onto the lawn before seeking refuge myself. Now, I’m okay with digital files instead of physical prints. I still have files upon files of papers from my grad school and teaching days, but much like my photos, if I could get them all scanned and searchable, it would be a joy to cart them to the recycling center. And I’m even adjusting to not owning a physical object that contains my music and makes it portable. I might even believe in The Cloud someday.

But I have a collection of precious objects that I’m not willing to part with. They come from creators and givers who’ve provided years of joy and inspiration. Many of them are signed books or CDs, inscribed with my name and personal messages. I’ve had people in line tell me that I was an idiot for asking for personalized signatures–“It’s worthless now!” they said as they saw my name on it.

But I have a collection of precious objects that I’m not willing to part with. They come from creators and givers who’ve provided years of joy and inspiration. Many of them are signed books or CDs, inscribed with my name and personal messages. I’ve had people in line tell me that I was an idiot for asking for personalized signatures–“It’s worthless now!” they said as they saw my name on it.

They couldn’t be more wrong.

Relics are common in every world religion, but they play a unique role in Christian belief. Because Jesus’ death and resurrection are the primary incidents of divine intervention at the core of the faith, it was believed that saints who chose to die for their faith rather than save themselves through abjuration were touched by God at the moment of their deaths as well. This transformed the graveyards of martyrs from unclean and unlucky places into the homes of the divinely touched dead. The celebration and white clothes of early Christian mourners, as they paid homage in the unsafe burial grounds outside city walls, made ancient pagans very uncomfortable, yet another reason they rejected the Jesus cult for so long.

Ancient people also believed that the location of a past miracle actually raised the chances of another miracle occurring in the same place, rather than our modern notions of lightning never striking the same place twice. If death is the ultimate miracle, than the remains of the dead become the ultimate location for a potential repeat. And the fact that those remains made that miraculous location physically portable was just the icing on the morbid cake. If you could carry an object with you that made you more likely to have a personal experience with God, it’d be hard to pass that up.

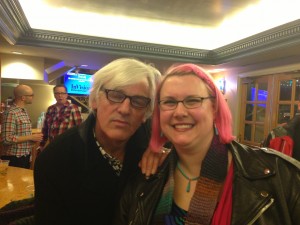

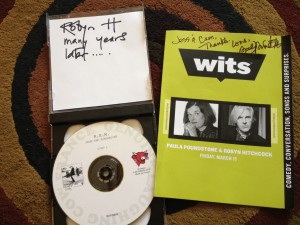

I’m certainly not claiming that any of the objects that mean so much to me are divine connections, but they do serve as concrete links to to a moment of human contact I shared with someone I love and admire. Friday night, Darling Husband and I went on a date to see a radio show taping featuring comic Paula Poundstone and musician Robyn Hitchcock (of The Soft Boys and the Egyptians fame). Robyn’s music was part of the soundtrack of my high school and college years, and Paula’s comedy was one of the earliest bonding experiences with the DH after he moved to the States 16 years ago. I had stuffed my two favorite CDs and a Pretty Good Joke Book from Prairie Home Companion into my tiny purse, on the off chance that we got to meet them, but after waiting for more than a half-hour after the show, it seemed less likely. I bugged one of the staff members, explained how one of the CDs was an incredibly rare bootleg of a concert booked under a different name. They said Paula was probably taking off, but Robyn would be out in a bit.

So when both came out the door, I sort of blanked. I totally forgot about the Joke Book, and started telling her about how the DH and I met, and the funny lines that have become in-jokes between us. She seemed genuinely pleased, thanked us for the kind story, and happily signed our show program to the both of us. With Robyn, I had a whole extended conversation about the bootleg, and the cover art of the other CD which had been modified in the second pressing, and as random and delightful a variety of subjects as I would hope from the godfather of surreal UK proto-punk and alt-pop. I explained how my boys enjoyed when I sang one of his songs to them, and he scrutinized the picture of them I showed him. He asked their names, and took a funny picture with me.

So when both came out the door, I sort of blanked. I totally forgot about the Joke Book, and started telling her about how the DH and I met, and the funny lines that have become in-jokes between us. She seemed genuinely pleased, thanked us for the kind story, and happily signed our show program to the both of us. With Robyn, I had a whole extended conversation about the bootleg, and the cover art of the other CD which had been modified in the second pressing, and as random and delightful a variety of subjects as I would hope from the godfather of surreal UK proto-punk and alt-pop. I explained how my boys enjoyed when I sang one of his songs to them, and he scrutinized the picture of them I showed him. He asked their names, and took a funny picture with me.

By the time we left the theater, I was shaking and teary at how kind and engaged both stars were to an obviously flustered mega-fan. And I was holding onto two more precious relics. They’ll never show up on eBay or any other fan site for sale; their meaning is entirely personal. But whenever I touch them and look at the inscriptions, they collapse the time between when those marks were made and when I’ll be in the future, bringing the joy and miracle of human contact fully back into the material present.

People are right that I don’t need objects or photos to remember important moments. There’s no doubt I’ll remember that moment any less clearly in 20 years than what I had for breakfast the morning before. My autistic memory is indelible and visual, so it’s even less trouble for me than for many people to pull up the images and conversations that left deep impressions. But my brain is also highly sensitive to sensory memory, so the touch of a CD jewel box, or the sound of a mixtape, or a porcelain statue, or the silky pages of a graphic novel evoke an even stronger sense of time and place.

These precious objects perform the miracle of bringing past joy into the present; that magic is wrought through the application of a Sharpie and a moment of human interaction. And as my collection of relics grows, I know that I could no more part with these attachments than with the experiences that created them.

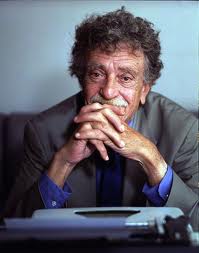

When I was in college, I had the great good fortune to see Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. speak on campus. He was as hilarious, irreverent, and insightful as his books. I wish I remember more of what he discussed, but just one thing has survived the years and leaks of memory.

When I was in college, I had the great good fortune to see Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. speak on campus. He was as hilarious, irreverent, and insightful as his books. I wish I remember more of what he discussed, but just one thing has survived the years and leaks of memory.

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con.

This year, I’m trying to do something about this. I’ve submitted proposals to both Origins and Gen Con–the two conventions I’m planning to attend this year–to establish a Sensory Break Room for people who are physically or mentally challenged by the rigorous environment of the con. The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.

The room will be screened off, instead of requiring users to open and close a clanky door. The lights will be kept quite low, probably too low to read properly, but there may be some soft, shifting colored lights to focus on. No music or other noise will be permitted, but a small fan or ionizer will run to provide white noise as an auditory buffer. Nobody will bug anyone else, but neither is it a nap room. If someone falls asleep, the monitor will wake them up after five or ten minutes, and each user will be responsible if they accidentally sleep through an event they’re supposed to attend. I’m hoping that the folks most likely to use it will be generous in bringing some adaptive tools to share–weighted blankets, exercise balls, fidgets, and other comforting objects.

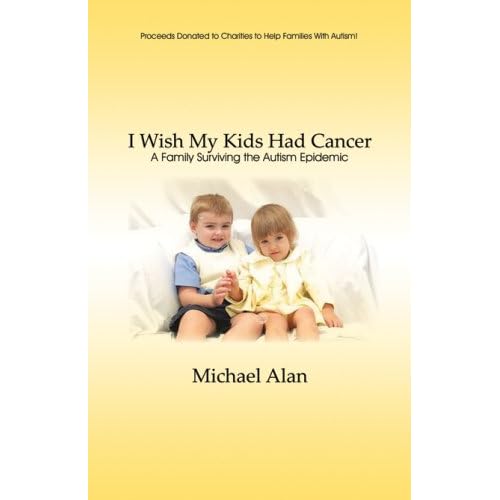

I know the Internet is designed to inspire fury. That hasn’t been the majority of my experience with it, but lately, it seems determined to correct my underestimation of its rage-inducing qualities.

I know the Internet is designed to inspire fury. That hasn’t been the majority of my experience with it, but lately, it seems determined to correct my underestimation of its rage-inducing qualities. PROBLEM #3: HE THINKS THERE’S ONLY ONE WAY TO PLAY WITH TOY CARS. This one particularly burns my ass, because I know from experience that he’s wrong. When I was a kid, I played with toy cars by lining them up in perfectly symmetrical, parallel rows, sorted by shape, size, and color. Then my sister would walk through the lines like Godzilla, kicking them to kingdom come. And then I would line them up again in different patterns. I picked my favorites by the way they felt in my palm, my closed fist.

PROBLEM #3: HE THINKS THERE’S ONLY ONE WAY TO PLAY WITH TOY CARS. This one particularly burns my ass, because I know from experience that he’s wrong. When I was a kid, I played with toy cars by lining them up in perfectly symmetrical, parallel rows, sorted by shape, size, and color. Then my sister would walk through the lines like Godzilla, kicking them to kingdom come. And then I would line them up again in different patterns. I picked my favorites by the way they felt in my palm, my closed fist.

The time for ritual is at hand. I stand in the place of my power, tools of the magic I will work laid out before me– silver, wood, and steel. Fire and water are at my command, earth and air held back by my will. In this time, I will draw on the forces of creation, shaping elements. Here, I am an alchemist, a hand of the goddess herself.

The time for ritual is at hand. I stand in the place of my power, tools of the magic I will work laid out before me– silver, wood, and steel. Fire and water are at my command, earth and air held back by my will. In this time, I will draw on the forces of creation, shaping elements. Here, I am an alchemist, a hand of the goddess herself. While I am not so bold as to commit to such a statement myself, the power of the kitchen, and what it summons and creates, is not to be denied. Though I began down the path of Wicca in solitude, I learned the magic of cooking as all good magics are best learned : at the elbow of a wise and laughing grandmother. The rules were simple. Wash your hands. Clean as you go. Read the whole recipe before you start. Measure with care. And, most importantly, share the joy as often as possible–that’s why there are always enough beaters and spatulas and bowls for everyone. If you abide by that last rule, no spills or scorches can spell failure. Just vacuum up the oatmeal, wash the egg out of your hair, and laugh about the fun you had.

While I am not so bold as to commit to such a statement myself, the power of the kitchen, and what it summons and creates, is not to be denied. Though I began down the path of Wicca in solitude, I learned the magic of cooking as all good magics are best learned : at the elbow of a wise and laughing grandmother. The rules were simple. Wash your hands. Clean as you go. Read the whole recipe before you start. Measure with care. And, most importantly, share the joy as often as possible–that’s why there are always enough beaters and spatulas and bowls for everyone. If you abide by that last rule, no spills or scorches can spell failure. Just vacuum up the oatmeal, wash the egg out of your hair, and laugh about the fun you had. But I have to be honest about something, and it’ll probably blow the lid right off any sort of “kitchen witch mystique” I may have managed to build. I am no gourmet. I’ve never taken a cooking class. Those brownies which my friends and co-workers steadfastly maintain are the best they’ve ever tasted? Betty Crocker, Fudge Supreme, $2.49 with coupon. That chili whose aroma wafts out like tickling fingers when I open the door on a cold winter night, drawing my husband in all the quicker? Packet of spices, canned beans and tomatoes. Simmer on low for 20 minutes. That’s it. And I’ve never made a secret of it.

But I have to be honest about something, and it’ll probably blow the lid right off any sort of “kitchen witch mystique” I may have managed to build. I am no gourmet. I’ve never taken a cooking class. Those brownies which my friends and co-workers steadfastly maintain are the best they’ve ever tasted? Betty Crocker, Fudge Supreme, $2.49 with coupon. That chili whose aroma wafts out like tickling fingers when I open the door on a cold winter night, drawing my husband in all the quicker? Packet of spices, canned beans and tomatoes. Simmer on low for 20 minutes. That’s it. And I’ve never made a secret of it. So I may not always remember all the poetic invocations when I call the Watchtowers in a Circle, but I remember the favourite food for every loved one in my life, and most of the recipes. And so I might be dreadful at keeping a proper herbal grimoire stocked–my spice racks are the envy of all who survey. I consider myself well on the road to the Lord and Lady’s wisdom, because I know the seat and value of a generous, abundant power within myself, one of the greatest signposts on everyone’s spiritual journey. And when I get there, I’ll be sure to have a dish to pass.

So I may not always remember all the poetic invocations when I call the Watchtowers in a Circle, but I remember the favourite food for every loved one in my life, and most of the recipes. And so I might be dreadful at keeping a proper herbal grimoire stocked–my spice racks are the envy of all who survey. I consider myself well on the road to the Lord and Lady’s wisdom, because I know the seat and value of a generous, abundant power within myself, one of the greatest signposts on everyone’s spiritual journey. And when I get there, I’ll be sure to have a dish to pass. Friday is the Autistic Day of Mourning, a day to honor the autistic people who have lost their lives to the desperate or careless actions of parents and guardians, or to the crushing weight of the sensory world that seems inescapable by any other means but death.

Friday is the Autistic Day of Mourning, a day to honor the autistic people who have lost their lives to the desperate or careless actions of parents and guardians, or to the crushing weight of the sensory world that seems inescapable by any other means but death.